ILLUSTRATION BY ELLIS ROSEN

On a Friday night this spring, I reported to the inaugural show at

Fisher Parrish Gallery, in Bushwick. Some awfully cool looking folks were packed into the small white space. The table was laid with 117 new examples of paperweights. Almost none of them resembled the office accoutrement of last century, when open windows and fans sent paper sailing through reeking cigarette fog. These were objet d’art. They ranged from the purely ironic (a furry outgrowth) to the purely beautiful (chain links encrusted in sherbet crystals). Many were ineffable abstracts, and a few were just satisfying (animal figurines drilled into each other). “My life doesn’t justify a paperweight,” a girlfriend remarked. “My life isn’t settled enough. You don’t buy one until you think you’re not going to move.”

Paperweights had never struck me as markers of stability. But a month later, when I was laid off from the legacy media company where I worked for a print magazine, I surveyed my desk, picked up a stack of our branded notepads and a handle of whiskey and thought, At least I don’t have to lug no paperweight.

Then Saturday came without Saturday’s feel. In a vintage shop, I drifted from taxidermy pheasants to a shelf staged with dusted curio, and there was a Murano blown-glass paperweight. At its center, the softball-size bubble had a clear tubular ring, inside of which was a clear finial shape from which streaks of red sprayed in arches at 360 degrees. The thing was maybe five pounds? My fiancé found me cradling it to my heart. “You’re going to bring that home, aren’t you,” he said, meaning: Did my foolhardy troth to paper in the age of new media know no bounds? The paperweight seemed to englobe our opposed perspectives: he thought it looked like a nasty vortex; I thought it looked like a wine fountain.

In 1495, a historian from Venice remarked, “But consider to whom did it occur to include in a little ball all the sorts of flowers which clothe the meadow in Spring.” He was referring to the glasswork techniques the Romans had picked up from the Egyptians. The results were not paperweights, not least because the bottoms had not yet been shaved flat to prevent rolling. That was an evolution Paul Hollister, the late authority on paperweights, likened to “turn[ing] the Venetian pumpkin into Cinderella’s golden coach.” (As a bonus, grounding the base removed the pontil mark, the scar from a glassblower’s iron rod, and without a belly button, the orb seemed to come into the world by magic.)

Three and a half centuries later, in 1845, a glassmaker named Pietro Bigaglia showed off his “Venetian balls” at the Austrian Industrial Fair, in Vienna. The earliest paperweight we know of dates to that year. French fair-going glassworkers—wishing to goose their depressed industry—ran with the idea. It was just three years before the February revolution and the creation of Napoleon’s Second Republic. The time was right. With affordable paper and dependable mail services, letter writing had become a newly popular pastime, and something had to keep those sheets in order. Glasshouses like Baccarat, Saint-Louis, Clichy, and Pantin revived ancient techniques such as flame working, filigree, and millefiori, “thousand flowers” wrought from brightly colored glass canes; they also perfected plant and animal motifs. These paperweights were useful, fashionable, relatively inexpensive, and cheery (a way to keep flowers on desks even in winter), and their manufacture spread through parts of Europe. Immigrant glassworkers brought the trend and their know-how to America. But by 1860, the bauble-bubble was cooling off.

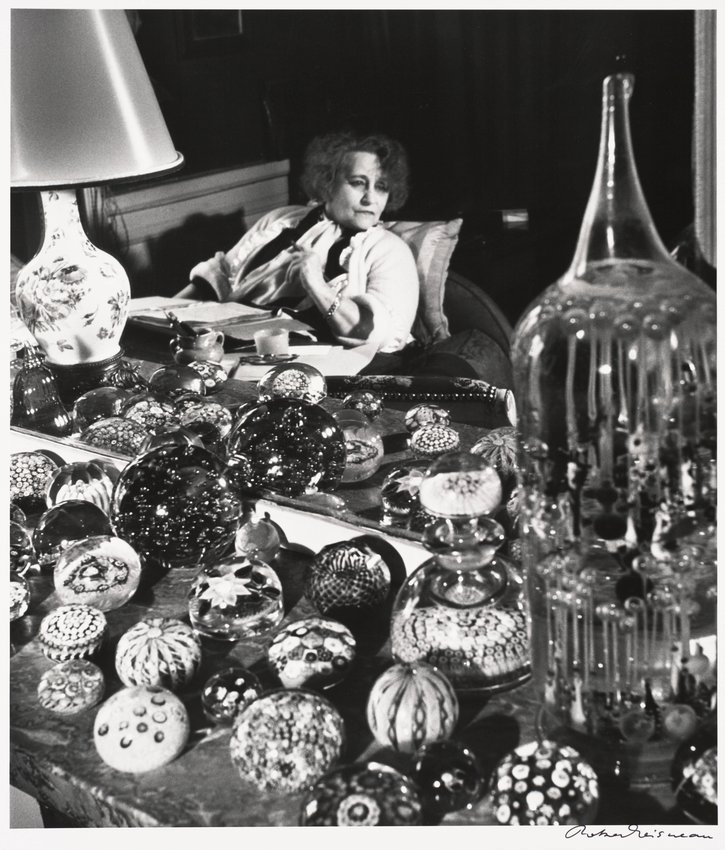

In the late forties, Jean Cocteau arranged for a young Truman Capote to have tea with Colette at her apartment in Paris. They did not manage to discuss literature; instead, Capote was moonstruck by the Frenchwoman’s collection of valuable antique paperweights, which she called “my snowflakes”:

There were perhaps a hundred of them covering two tables situated on either side of the bed: crystal spheres imprisoning green lizards, salamanders, millefiori bouquets, dragonflies, a basket of pears, butterflies alighted on a frond of ferns, swirls of pink and white and blue and white, shimmering like fireworks, cobras coiled to strike, pretty little arrangements of pansies, magnificent poinsettias.

MADAME COLETTE, WITH SOME OF HER PAPERWEIGHTS, IN 1950. © ROBERT DOISNEAU.

Colette suggested she might take them with her in her coffin, “like a pharaoh.” When she gave a Baccarat with a single white rose inside to Capote, he caught the fever. He sought paperweights at auctions in Copenhagen and Hong Kong. Once, he found a four-thousand-dollar weight in a junk shop in Brooklyn for which he shelled out just twenty bucks. In East Hampton, he successfully bid seven hundred dollars for a millefiori (“the real thing,” “an electrifying spectacle”) worth seven grand.

At home, my weight immediately found its use. When you are a paperweight, you have one job, and it is so easy. In theory, any lousy rock could do it: be heavy (glass, crystal, marble, brass, and bronze have been standard issue), be flat-bottomed (spheres, pyramids, cubes, and discs tend not to topple), and sit pretty (on this last point, common geology would fail). If you can do that, you are doing great. Layoffs still involve paperwork, which, once printed, generally has to get notarized and posted; such documents can stagnate on your desk, along with odd to-do lists, tear sheets, bills, and greeting cards. But I found none of it was to be easily ignored or mislaid when it was pinned down by this shroom of glass that catches and carnivalizes the sky.

Last year, Christie’s mounted Dress Your Desk, an online auction of dozens of paperweights that had belonged to Arnold Neustadter, the inventor of that other once-ubiquitous desktop accessory, the Rolodex. He was “the most organized man I ever knew,” his son-in-law told an obit writer. Adding, “Whenever anyone put something on his desk that didn’t belong there, he’d move it.”

Carleigh Queenth, head of ceramics at Christie’s, told me, “He had a really lovely collection, including some incredibly rare pieces like a Pantin salamander weight.” Only twenty of those are known to exist, and only extreme talent could have pulled off the forms, textures, and patterns (e.g., polka-dotted amphibian bod on floor of sand and lichen). A prior director of the

Corning Museum of Glass, which has assembled one of the most important exhibitions of paperweights, regards these salamanders as “the greatest technical achievements of nineteenth-century paperweight makers.”

The French paperweight heyday, between 1845 and 1860, remained the high-water mark for the industry for nearly a hundred years. Then in the sixties, in America, the studio-glass movement relocated glassmaking from factories to ateliers, where utility gave way to art. Art schools started to teach glasswork. Galleries started to show glasswork. And

Paul Stankard, according to Queenth, “was one of the first contemporary glass artists to elevate paperweights to an art form.” Stankard is a living master, unrivaled. “While flowers in nineteenth-century weights can be somewhat cartoonish,” she said, “his are always incredibly accurate, like botanical studies.” She pointed to Stankard’s bees. “You can practically hear them buzzing.”

PAUL STANKARD, FIELD FLOWERS CLUSTER WITH HONEYCOMB AND SWARMING HONEYBEES ORB, 2012. PHOTO: © RON FARINA

When I phoned the seventy-four-year-old artist at his studio in southern New Jersey, he told me that, under the effect of an eighteen-hundred-degree flame, hot glass is viscous, “like honey.” He had attended a vocational school and begun his career blowing bespoke glass equipment for chemists. “It was a good trade, but I wanted to be creative.” He imagined suspending the flowers of Delaware Valley from his childhood—he’s a Walt Whitman devotee—in glass. He drove up to Corning and studied the antiques. In 1972, he left his job to become a full-time paperweight maker. Stankard weights are transcendent. “But you’re welcome to put them to work if you want to,” he said. “They’ll keep paper down.”

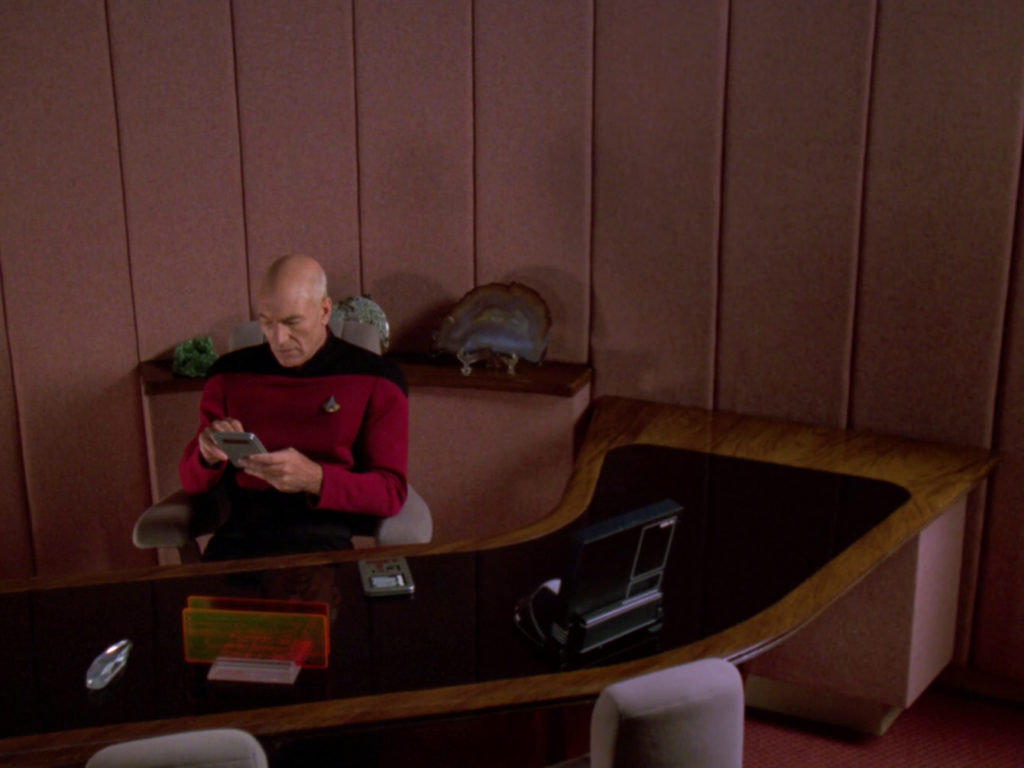

While my paperweight helps me mind the gap between the analogue and digital worlds, perhaps paperweights will never become obsolete, even in the twenty-fourth century, when human society will have gone paperless, at least in outer space and according to

Star Trek: The Next Generation. Even so, it is something to notice a shard-like crystal on the desk of Captain Jean-Luc Picard. The iconic prop appears in nearly eighty episodes. It is not technology. It does nothing—although Picard often handles it while mulling over tough decisions or speechifying, in such a way that the crystal recalls Yorick’s skull. Trekkers have

painstakingly attempted to re-create the hunk in casting resins. No one knows what became of the original from set.

CAPTAIN PICARD’S DESK IN HIS READY ROOM ON THE USS ENTERPRISE-D (1989, OR 2365).

Roddenberry Entertainment—named after the creator of the original

Star Trek television series—offers

a faithful ninety-nine-dollar lead crystal replica on its web shop. The prop’s geometry, the product description says, “was obsessively reconstructed using digital 3-D modeling software, referencing and reconciling hundreds of film frames of the crystal’s appearances across the seasons of

TNG.” (Ryan Norbauer, a software engineer whose résumé includes stints at

NASA, the Center for Disease Control, and British Parliament, was on the project.) “It’s a great way to add a bit of commanding gravitas to your workspace, whether that’s the ready room of a starship or a tabletop at a café.”

Roddenberry’s director of consumer products, Brent Beaudette, told me they made a run of five hundred Picard desk crystals. About half have sold since they were released in August. I asked Beaudette if he thought the show’s set designers, in imagining the future, might have retained a vestigial paperweight. He said, “Our overall consensus is that it serves as a device to relieve tension or stress through simple repetitive movement. However, we can only speculate as to the original intent.”

Worrying my weight with my left hand, I thought back to Capote. He traveled with his paperweights in a black velvet bag, taking as many as six of them, even on two-day trips to Chicago. They were a comfort, he explained.

Chantel Tattoli is a freelance journalist. She’s contributed to the New York Times Magazine

, VanityFair.com, the Los Angeles Review of Books

, and Orion

, and is at work on a cultural biography of Copenhagen’s statue of the Little Mermaid.

:focal(991x1133:992x1134)/https://public-media.smithsonianmag.com/filer/79/09/7909bd7a-a783-4583-93ac-6b260b5509d2/oct2017_i09_calder.jpg)