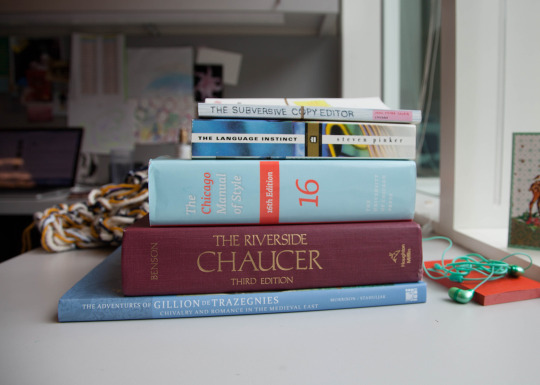

5 books on Editing and LanguageA Shelfie from Ruth Evans Lane, Editor in Getty Publications.

Hi, I’m Ruth Evans Lane, associate editor in Getty Publications. I really like books, and I would gladly discuss language with you any day of the week. These are five books that have pushed me to think about language in different ways.

A second edition of this book just came out this last year, which I haven’t yet read, but this is an essential companion to the editor’s bible, The Chicago Manual (see below). The demands on an editor can feel overwhelming, but Carol Fisher Saller, an editor of The Chicago Manual, breaks it down in a hilarious (I promise!) and helpful way.

Steven Pinker is a cognitive scientist and linguist at Harvard, and I read this book during a truly formative time in my life—right after I finished college. I was an English major, budding editor, and insufferable pedant. Pinker completely changed the way I thought about language—you won’t catch me telling anyone irregardless isn’t a word (though if you see it in one of the books I’ve edited, know that I’m lying dead somewhere).

In my world, there is no higher authority. The Chicago Manual (CMOS) is my alpha and omega. As art editors, we from time to time follow different conventions than those set forth in CMOS, and I’ve never met a rule I wouldn’t consider breaking, but I consult this book every single day (though, more often than not, their online edition), and when I was doing my copyediting certificate at UCSD Extension, I read it cover to cover.

If anyone ever tells you that there’s a right way spell a word, well, they should spend some time looking at medieval English. English didn’t really have standardized spelling until well into the 18th century, and even today, spellings are still changing, though less dramatically than they once did. One of the most interesting things to me about Chaucer is that he is, along with Dante, the most famous early vernacular writer (vernacular in this context means the language of the common people, so English for Chaucer and Italian for Dante). During the Middle Ages in England, most texts were still written in Latin, and French was spoken at court; Chaucer and Dante (and other, less-known writers before them) were not just brilliant writers but true revolutionaries.

This is a book I edited for the Getty and it’s special to me not just because the authors were tremendously fun (see this trailer for the book) but also because it’s about an exquisitely beautiful illuminated manuscript in the Getty’s collection that also happens to be written in vernacular French (which you can hear Zrinka reading here). Most of the medieval manuscripts in our collection are religious and written in Latin, so this Middle French tale of the love affairs and adventures of a medieval knight during the Crusades is extra special. This book, which gives the truly stunning illuminations along with a translation from Middle French, also provides a fascinating account of the manuscript’s cultural and political context and an in-depth art historical analysis.

No comments:

Post a Comment