Age of Emancipation

One of France’s most influential contemporary thinkers, Marcel Gauchet manages to craft a compelling historical account of half a millennium, exploring how we arrived at today’s crisis—and how we might get out.

L’Avènement de la démocratie (The Advent of Democracy Series) I–IV

by Marcel Gauchet

Gallimard, 2007–2017

by Marcel Gauchet

Gallimard, 2007–2017

Once upon a time, it was not unusual to think that history was a story. Some held that history was the ordeal to which mankind was subjected while awaiting the apocalypse; others saw it as the triumph of human reason over ignorance and prejudice. Hegel considered it to be humanity’s ever-growing consciousness of freedom; Marx argued that it was a tale of class conflict, culminating in revolution. These days, however, the notion that the historical process might consist of a single grand narrative is almost universally regarded as little more than a comforting myth.

Marcel Gauchet disagrees. For over a decade, the French historian and philosopher has devoted himself to a mammoth four-volume work premised on the unapologetic affirmation that history has a meaning. As its title, The Advent of Democracy, suggests, the project is an attempt to explore democracy’s fate in Europe and (to a lesser extent) in North America. Gauchet begins this story in the early modern period and takes it up to our neoliberal present, where the demise of a sense that history possesses an overarching meaning is one casualty in a broader dissolution of collective attachments. In our neoliberal age, democracy has come to mean little more than the pursuit of individual rights and interests, while the hope of determining our shared fate through democratic means has become strangely elusive.

To think ourselves out of this mindset, we need history—and lots of it. Each successive volume of Gauchet’s magnum opus is significantly longer than its predecessor, often while covering a shorter period. The first volume, The Modern Revolution (La révolution moderne, 2007), considers the rise of the early modern state through to the development of nineteenth-century liberalism in just over 200 crisply argued pages. The next volume devotes slightly more than 300 pages to assessing The Crisis of Liberalism (La crise du libéralisme, 2007) that lasted from approximately 1880 to 1914. The third installment is longer than the first two volumes combined: though The Totalitarian Ordeal (À l’épreuve des totalitarismes, 2010) examines the period between 1914 and 1974, the vast majority of its 650 pages are devoted to the dictatorships that flourished in Europe between 1922 and 1945. Now, after a seven-year gap, Gauchet has published the final volume, The New World (Le nouveau monde, 2017). To explain our present epoch, Gauchet requires no less than 768 pages.

Do we need yet another history of democratic ideas, institutions, and practices? And why now? Writing ten years ago, Gauchet observed that democracy had become “the unsurpassable horizon of our time.” Could a history—not to mention a philosophy of history—driven by such an insight be anything other than insipidly celebratory?

Gauchet manages to avoid this. Instead, he has written a work that is both a compelling historical account of half a millennium and a trenchant work of cultural criticism. Much of the reason for this is his idiosyncratic understanding of “democracy.” The term, in his eyes, is about more than elections and multiparty systems or human rights and the rule of law. It is, rather, the most coherent and complete form of the fundamental impulse that Gauchet believes propels human history: the drive for what he calls “autonomy.” Derived from the Greek words autos (self) and nomos (laws), autonomy literally means the capacity to make one’s own rules, to self-legislate. For Gauchet, it refers to an overriding human aspiration: to become the master of one’s own fate.

Thus the story of history, for Gauchet, is that of humanity’s long and gradual emergence from a state of “heteronomy”—in which we believe ourselves to be governed by some transcendent, non-human “other” (hetero)—to a condition of autonomy. In modern times, he contends, democracy has become autonomy’s primary vehicle. But, according to Gauchet, the triumph of autonomy has led to a crisis for democracy. Our age of emancipation is also one in which individuals and even whole societies feel oddly powerless. Heteronomy is gone. Yet, once again, we have lost control.

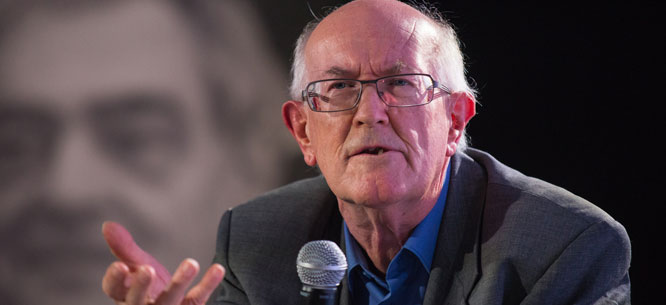

Though he is one of France’s most influential contemporary thinkers, Marcel Gauchet has had little discernible impact in the United States. He taught for many years at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris. He is also the founder and editor of Le Débat, one of France’s most prominent general-interest journals, in addition to having worked as an editor at Gallimard, the prestigious publishing house. But even in France Gauchet remains an elusive—and aloof—figure. He became a prominent academic, attracting throngs of visitors to his weekly seminars, without ever earning a doctorate. He is an admired, widely read public intellectual who is prone to caustic, even vicious polemic. Most puzzling of all are the politics of this deeply political thinker: he rose to prominence by championing liberalism over Marxism, yet is a staunch critic of human rights and individualism. He is a self-described philosophical socialist, but is often accused of being a conservative, even a reactionary.

Compared to many French intellectual mandarins, Gauchet’s background is also atypical. He was born in 1946 to a modest family in rural Normandy. As a child, he served as an altar boy. Following a well-traveled path of upward mobility, he studied to become a teacher. Along the way, he discovered politics. Early union activism brought him into contact with communists, for whom he developed a visceral distaste. Even so, he became fascinated with Marx and, more generally, the burst of revolutionary literature that appeared in the heady political atmosphere of the late sixties, which culminated in the student and worker riots of May 1968. Gauchet taught school for a few years, before deciding to devote himself (supported by menial jobs) to the study of philosophy.

The key to Gauchet’s thought lies in his reaction to May ’68. Many students who had marched in the streets considered themselves Marxists; yet Marxism, Gauchet believed, is precisely what ’68 had disproved. The tumult of the sixties, Gauchet concluded, had not sprung from the contradictions of capital. Against the conventionally Marxist focus on economics, Gauchet emphasized the primacy of politics. And in contemporary Western societies, this meant the primacy of democracy.

The key figure in Gauchet’s intellectual development was the philosopher Claude Lefort, a former Trotskyist and member of the post-Marxist circle Socialisme ou Barbarie, whom Gauchet met in the late sixties. Lefort’s philosophy hinges on the distinction between “politics”—the competition for and exercise of power—and the “political,” which he defined as the symbols societies use to render social relations tangible. In a divine-right monarchy, for example, the king’s body is said to coincide with the body politic. But the unity suggested by the king’s body—one people, one body—is a myth. No symbolic wrapping can ever encompass a society in all its diversity. Specific groups may seek to impose a particular meaning on a community, but such efforts are destined to be temporary and incomplete. According to Lefort, the only political system that recognized this basic truth was democracy.

Gauchet drew on Lefort’s insight to mount a vigorous attack against Marxism. What Marxism cannot abide, he argued, was the indeterminacy, the “empty space” at the heart of the political: something—the working class, the party, or Uncle Joe—must fill it. Marxism is, in short, haunted by the idea of a unified society. This fantasy, Gauchet contended, is what makes Marxism dangerous. Along with a small vanguard of other intellectuals—notably the historian and political theorist Pierre Rosanvallon—Gauchet became a key figure of the so-called anti-totalitarian movement of the mid-1970s, which sought to purge the left of its vestigial Marxism.

Gauchet moved beyond merely attacking Marxism in his 1985 work, The Disenchantment of the World. This “political history of religion,” to quote its subtitle, presented democracy as the culmination of the process of “leaving religion”—la sortie de la religion. Only in primitive society, he argued, does religion exist in its purest form. Hunter-gatherer societies are founded on a communal decision to deny that they have any control over their own fate. Whatever happens to them is attributed to a supernatural other, be it a totem animal or nature spirit. Everything changes with the appearance of the state. Through the state, humans acknowledge themselves as the authors of their own destiny. The beginning of the state initiates, in his view, the disenchantment of the world. It is a kind of sociological big bang, obliterating the static world of heteronomy and unleashing autonomy’s expansive energies.

According to Gauchet, genuine autonomy can only be achieved by a politics that recognizes the importance of liberty but renounces the fantasy that society can be refashioned at will. The solution, in a word, is liberalism. When combined with his emphasis on democracy, this triumphant history of liberalism made Gauchet a major figure in France’s liberal turn. Yet he expressed increasing unease with contemporary culture. In particular, he worried that French society was being overtaken by a dangerous breed of individualism. Examining what he saw as the contemporary obsession with human rights, environmentalism, education, and new religious fads, he detected a new type of individualism, fixated on self-realization, identity, and personal fulfillment. Individualism of this variety did not nurture democracy, but risked undermining it by sucking meaning out of public life. It is in this sense that Gauchet’s conception of history is radically un-Hegelian: the path of autonomy leads not to ever higher forms of unity, but to increasing fragmentation. Francis Fukuyama’s notorious claim that democracy represented the “end of history” was not, Gauchet contended, entirely wrong. But precisely at this moment, democracy seemed weak, unappealing, and often impotent. In its hour of conquest, democracy was adrift and unloved.

The Advent of Democracy is Gauchet’s monumental effort to explain this problem. The four-volume work risks the fate of such sprawling, late-career statements as Sartre’s The Family Idiot (1971–1972) or Voegelin’s Order and History (1956–1987): books that are admired, but rarely read. This would be a shame. Gauchet’s masterpiece offers the kind of sweeping view of modern European history that one finds in Hobsbawm’s “Age of” series, topped up with a quasi-Hegelian philosophical perspective. Let us briefly consider its main arguments.

To understand why democracy is in crisis, we must first understand modern democracy’s nature. Contemporary democracy, Gauchet argues, fuses autonomy’s three modern dimensions. It has a political form, that of the nation-state; a juridical form, of human rights; and a temporal form, defined by a consciousness of history as the outcome of collective action. Individual autonomy enshrined in rights makes the nation-state the only adequate form of collective autonomy, and history is the means by which individuals and nation-states make sense of their experience. Democracy’s fate, for Gauchet, lies in how these attributes have evolved over time.

Gauchet believes that every historical moment lies somewhere on the spectrum between heteronomy and autonomy. The goal of the French Revolution, for example, was to reimagine political power on the basis of individual consent—to derive political authority entirely from the principle of individual rights. Yet in doing so, the revolutionaries unwittingly resurrected the principle of sacred unity, an incipiently totalitarian conceit. This ultimately explains the revolution’s recourse to terror as a way of purging society of elements that could not fit into an indivisible republic.

Nineteenth-century liberalism would emerge out of an attempt to rethink the revolution’s failed equation of rights and sovereignty. Genuine autonomy occurs when civil society—consisting notably (but not exclusively) of market relations—is separated from the state. Autonomy—and hence democracy—is achieved by separating legally independent individuals from the state, not by merging them. The discovery of society as a sphere that is distinct from the state also coincides, Gauchet believes, with the birth of historical consciousness: we begin to think historically when we recognize that the vector of human evolution lies not in the state, but in society.

By the mid-nineteenth century, liberals had achieved an intellectual synthesis consisting of three principles: the people, science, and progress. Their significance, for Gauchet, lies in the way each one tethers the desire for autonomy to a transcendent ideal. The people rule, but as a collective or national will, not as a cacophony of interests; the world is knowable to human reason, yet only insofar as it obeys the laws of nature; and history is the result of human action, which, it so happens, coincides with the quasi-providential will of progress. Liberty had “beat tradition on its own terrain.”

Then liberalism went through a crisis of its own. At the close of the nineteenth century, rapid social and technological change had fostered a sense that society was careening out of control. Politically, the development of parliamentary government only called attention to its long-windedness, inefficiency, and corruption. Society was, in short, pervaded by a sense that “we master [the world] less and less now that we are its sole masters.” Nationalists and socialists claimed to overcome liberalism’s endemic limitations with bold claims for the capacity of political action to organize society and tighten social bonds. Herein lies the paradox of the turn-of-the-century crisis: the further it advanced down the path of autonomy, the more it was tempted by a return to sacred unity.

The anti-liberal ideologies would, after the First World War, mutate into totalitarianism—the final, desperate gasp of the religious conception of society, a last-ditch alternative to liberalism. Yet the paradox of Soviet communism, Italian fascism, and national socialism was that each tried to bring an earlier social model back to life by using the resources of the very liberal democratic regimes they so despised. They sought, for instance, to overcome parliamentary inefficiency by incarnating political power in charismatic individuals. Yet rather than resurrecting sacred kingship’s idea of a power descending from heaven, totalitarian regimes rested on a distorted variation of the democratic principle that power emanates from the people. Stamping out God while invoking religion’s central motifs, totalitarianism, for Gauchet, was destined to spectacularly self-destruct.

But something unexpected happened on the road to liberalism’s triumph. It began with the initially unremarkable economic crisis of 1973. Stagflation forced Western governments to dismantle the residual collectivist principles they had embraced for several decades: government spending, full employment, and high wages became problems rather than solutions. Meanwhile, the crisis also marked the arrival onto the global stage of non-Western economic powers, like the OPEC countries and Japan: it was, in this way, globalization’s inaugural act. Labor, which had been integral to the Fordist model prevalent in the postwar years, was now viewed as costly and obstructive. Henceforth, finance and consumption would be the primary engines of economic growth.

For Gauchet, however, the transition to what became known as “neoliberalism” was about more than economics. It represented an across-the-board reconfiguration of social relations, which is perhaps best captured by the cultural fate of the computer. In the postwar years, computers symbolized the impersonality of a standardized, centralized world. In the sixties, Gauchet notes, IBM’s president predicted that, by the century’s end, there would be only five or six computers in the entire world. Instead, the personal computer, which registers our preferences as consumers while archiving our professional and intimate lives, has become the epitome of neoliberalism, a form of capitalism that purports to celebrate individuality and difference.

This social transformation had profound implications for the development of democracy. Where the postwar model had still assigned the state a significant role, neoliberalism tilts the scales heavily in favor of civil society, upsetting the delicate balance among individual rights, politics, and historical orientation that defines the modern mixed regime. Thanks to deregulation, privatization, free trade, and globalization, the economy is heralded as the dynamic force in society. Increasingly, the state is dismissed as an antiquated relic from a bygone era. With the twin eclipse of tradition and revolutionary aspirations, no particular historical goal seems to motivate our market-driven society, despite its obsession with innovation. “Moving forward” is just another way of saying “no future.”

The paradox, for Gauchet, is that neoliberalism’s founders had the political will and historical sense that contemporary neoliberal society sorely lacks. Both Thatcher and Reagan mobilized significant political support for their agendas, while claiming to reconnect with forgotten national traditions. In both cases, Gauchet writes, “politics was summoned to serve as its own negation”: government was needed to fix the fact that, as Reagan famously put it, “government is the problem.”

The United States, it is worth noting, plays an intriguing role in Gauchet’s argument. Not only does he make the relatively uncontroversial point that the United States is neoliberalism’s native home; he also suggests that Reagan was correct in seeing his program as deeply rooted in American history. For all the subtlety he displays elsewhere, Gauchet, on this topic, is a vulgar Tocquevillian: with no feudal past bearing down on them, Americans, whom he frequently describes as a “chosen people,” eased comfortably first into liberal democracy, then into neoliberalism (with FDR as little more than a passing fancy). This curiously Gallic take on American exceptionalism is almost completely silent on the role of race in American history—an oversight surprising even from the standpoint of his own framework. Gauchet’s game is always to show how the pursuit of autonomy gets bogged down by lingering commitments to an allegedly sacred hierarchy. What issue has exemplified this dynamic more in American history than race?

That is only one of the curious omissions in this nearly 2,000-page work. To pick only the most obvious example, the work is unapologetically Eurocentric. The chapter devoted to imperialism in the second volume considers Europe’s conquest of much of Africa and Asia in the nineteenth century as a reconfiguration of the religious notion of imperial unity. In volume four, Gauchet doubles down on his Eurocentrism, arguing that globalization is really the culmination of the indigenous European project of “leaving religion.”

As tempting as it is take potshots at this zeppelin of a book, however, we should not lose sight of how impressive it is that Gauchet’s project gets off the ground at all. He makes a sound case, however overstated it may be, that autonomy does allow us to grasp something profound about modern history—that it is a tug-of-war between efforts to give free rein to human volition, on the one hand, and to circumscribe human life by subordinating it to a transcendent power, on the other.

The new neoliberal dispensation, according to Gauchet, accounts for the curiously hollow tone of political life in Europe and North America in the eighties and nineties. “Democracy” came to refer to little more than individuals and their rights. Notions of the “common good,” “citizenship,” and “shared history” were viewed—sometimes by the right, sometimes by the left—with deep suspicion, as unacceptable infringements on personal freedom. The pursuit of individual autonomy as the ultimate justification of human life and social existence accounts for the growing distaste for politics and the waning sense of participating in a national history.

Our predicament is to live in a society that was devised as a solution to a problem we have forgotten. The democratic state once battled the church in a war over human life’s basic orientation. Democracy has won, at least in much of the world. But politics has been trivialized, losing the moral seriousness it claimed when religion was still a credible threat. So we live in a world of economic forces and individual interests made possible by the advent of democracy, but in the face of which democracy, at present, seems woefully impotent.

Democracy’s current challenges have triggered, like the crisis of liberalism at the turn of the twentieth century, attempts to overcome this sense of dispossession through leaders who, by incarnating the popular will, aspire to bring down corrupt and distant elites. Slogans like “Make America Great Again” could be seen as symptoms of the hollowness lurking within neoliberal society. Yet the paradox—most of Gauchet’s key insights are paradoxes—is that despite this palpable desire for greater political agency, many populists remain wedded to the narrowly economic conception of individualism that defines neoliberal society. Responding to complaints about his appointment of Goldman Sachs billionaire Gary Cohn as his chief economic adviser—“why did you appoint a rich person to be in charge of the economy?”—Trump said that we need “great, brilliant business minds . . . so the world doesn’t take advantage of us.” Even a populist whose entire politics is based on the inchoate belief that a nation has lost control of its fate can only propose, as a cure to this affliction, one of the illness’s original symptoms.

Once neoliberalism has knocked democracy off of its ledge, each of its three historic components—individual autonomy, the nation state, and history—offers a blueprint for putting Humpty Dumpty back together again. In the wake of the 2016 election, some on the left have argued that liberalism must once again become a full-throated political program, capable of mobilizing the nation around a collective vision of social transformation. Mark Lilla has, in this vein, criticized identity politics for succumbing to a philosophical individualism that is disturbingly Reaganite, and which, moreover, renders elusive any notion of the common good. Others maintain that the core problem of our society is its failure to ensure that citizens enjoy basic rights, not least because they can be targeted by demagogues. Thus Ta-Nehisi Coates has argued that the critique of identity politics (particularly when its upshot is a call to reconquer the white working class) really amounts to a kind of “white tribalism” that fails to recognize the “trenchant bigotry” that pervades American society. What Gauchet adds to the conversation is that this split between two conceptions of democracy—and the temporal horizons they imply—is precisely the challenge of reuniting, under neoliberalism, the different elements that make up democracy.

Ultimately, Gauchet’s work offers us, I think, two main lessons—both of which cut against the spirit of our times. First, we best understand democracy—and grasp its most vital impulses—when we understand it as a struggle, as a centuries’ long process whereby human beings reclaim powers they had once attributed to the gods. The tragedy of neoliberalism is that it has made us all Americans—in Gauchet’s admittedly problematic sense of a people to whom democracy came by virgin birth, with no pitched battle against a hierarchical or feudal past. Second, democracy is hard. Not in the conventional sense that citizenship requires commitment and effort. Democracy is demanding because it requires us to dispense with heteronomy, to which humans have often turned to solve many of their problems—including those arising from democracy itself. Can we live as autonomous beings, while recognizing the precariousness of this endeavor? Democracy’s fate, Gauchet teaches us, may hinge upon it.

Michael C. Behrent teaches history at Appalachian State University. All quotes translated from the French by the author.

No comments:

Post a Comment