Listening to Harold Bloom’s Laugh and DeLillo’s Bronx Accent

On listening to the archival audio of the Writers at Work interviews in the Morgan Library.

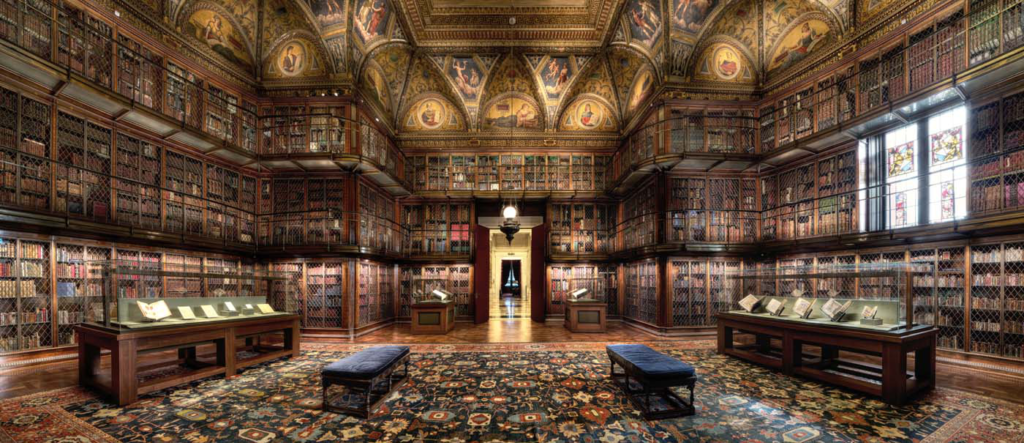

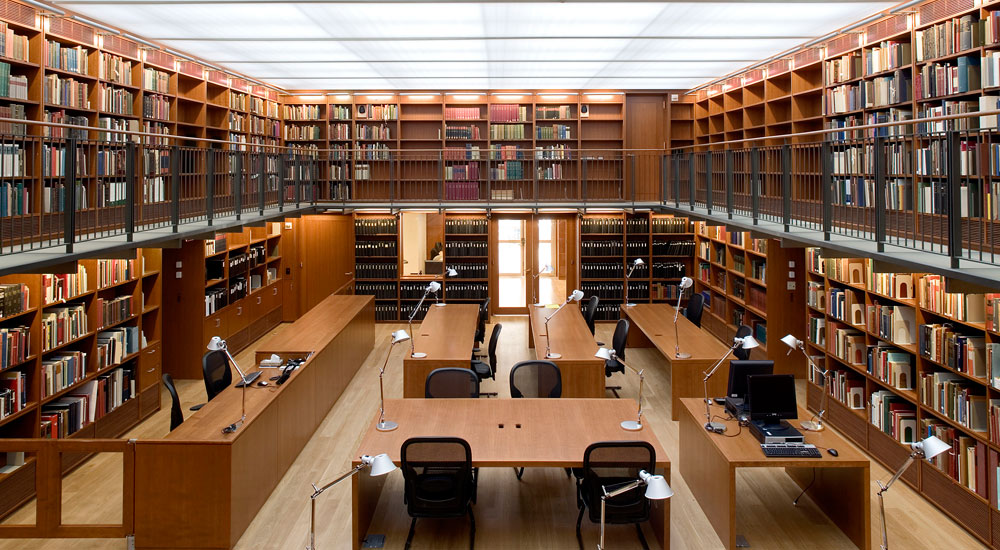

Every week for the past four months, I have made the multistage journey to the Sherman Fairchild Reading Room at the Morgan Library, the home of the archives of The Paris Review, in the aim of gathering audio for The Paris Review Podcast. I approach the library obliquely, around the corner from the main entrance, through the glass staff doors. I can see the guards, wave to them even, but each time, I must state my business through a small intercom at about the height of my belly button. When I am let in and signed in, I pass through a glass door that leads immediately to another glass door, which can only be opened by another security guard. Often, I am stranded for a few minutes in this transparent, soundproof vestibule, trying to get the attention of the guard. I can see perfectly into the open, mellow, well-lit blond-wood cube lobby of the library, which looks like something out of a Scandinavian modern Lego set. Then the door opens, and sound pours in—spoons tinkling on porcelain saucers, voices faintly echoing under the high ceiling, the tonic buzz of the HVAC system. The space changes. The sounds of footfalls or a cough or a machine whirr, I realize each time, constitute a room as much as the shape of a window, the sunlight slanting in, the style of a vase.

I trail behind the security guard to the elevators (all glass), a special key is inserted, and I rise to the third floor, where another glass-ended anteroom awaits. I can see through a glass door into the reading room itself, can see the employees moving in a shuffle that is itself a whisper, can see the researchers in their blue latex gloves gripping the corners of translucent manuscript pages with the delicacy used to pick up a strand of hair. I stuff everything I have except for my laptop, a notebook, and a number-two pencil (no ink allowed) in a locker and wash my hands, per regulation. Then the heavy glass door with a scratchy brass latch bolt clicks open, and I’m finally inside, and the room becomes the scent of aging books—stale glue, starchy paper, faint notes of smoked cigarettes and palms and rainwater—mingling with bright lemon cleaning products. In the reading room, I sit and listen to archival audio of The Paris Review Writers at Work interviews, which I have read and know the words to but only imagine I’ve heard, have been guessing at from across the transparency of the page.

The spoken and the written are different languages. Transcription is a sibling of translation. And just as translation is a zero-sum game—like saving possessions from a burning building, to pick up one thing, another must be dropped—so is transcription. Sound is sacrificed to sense, complex enthusiasms are coalesced into a single exclamation point, and fertile silence merely gestured at via lacunae on the page—em dashes, ellipses. Words are ripped from their native time. On the page, they are subjected to the tyranny of the reader’s pace, fast or slow. Things that are incomprehensible in writing are often perfectly comprehensible in speech. I dream of a system of fonts or diacritics to help us read transcripts like a musical score—one for the ascending staccato as people prepare to sneeze; one for the way people grandly echo the final phrase of somebody’s question to show that the interlocutor has finally gotten it; one for the casual hand wave that conveys boredom with a sentence as it’s being spoken; notation for all the hums, the uhs and ahs and wells that people string out as sentences are built in their heads and carry a preceding residue of the thought.

The Paris Review Writers at Work interviews are written things. They are extraordinary pieces of writing, but they are to the conversation itself as a piece of paper is to a tree. Whole exchanges are removed, chronology shifted, questions reframed, answers streamlined, personal remarks softened or excised. They flow like a piece of criticism, or a profile, guided by an editorial hand. From the centerless gestalt of the conversation itself— of which sound, smell, postures, the texture of the chairs, the temperature of the room are inextricable elements—the written interview is refined and sculpted into an artistic work. The raw audio is the conversation alive with its own formless logic—it is woolier, wilder, full of meandering digressions, sentences spoken over each other, the chance sonic interruptions that are the corona of everyday life. Like finally holding an object that I have long been gazing at, actually hearing the conversation is something of a revelation— the advent of a new color. The audio conversations are living things with all of the accidents and irrelevancies and fullness of existence. Lines that I recognized in print change when spoken—in speed, in intonation, in weariness or excitement. Some conversations have a chummy rapport, others an icy formality, others the stop-start rhythm of a first date. Some take place on stage, in public forums, others in private quarters. All are worth hearing.

There is, first, the surprise and delight of hearing the voices of authors whose works I know so well. In my head, Don DeLillo’s minutely observed, deep-system prophet prose and deadpan dialogue sound grave and gravelly, like somebody speaking from a dank subterranean room. In my ears, his recorded voice is sprightly, nasal, with a distinct Bronx accent. Hearing it shifts the way I read his work and opens up the grim humor in his writing that I had previously been deaf to. Italo Calvino gave his interview in Italian, and in contrast to his grinning playfulness in prose, his voice is slow, dragging, emphysemic. He shuffles along in a single breath to clasp on certain universally recognizable words—Italia, historia, fascismo—in the same way an arthritic dog circles and sits: gingerly, then all at once. Toni Morrison seems to be leaning very close to the microphone and speaks in a hush.

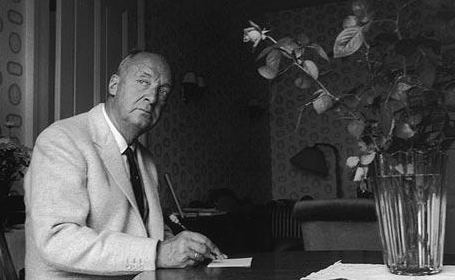

The vocal idiosyncrasies work like keyholes into a personality. The four-beat leitmotif that George Plimpton conjures out of the name Nabokov never fails to delight me in its voluptuousness—Nǝ (pause) Beau (pronunciation drawn out like an arch gossip columnist) Kavv (the fricative subtle, fading away like a comet tail). It corresponds perfectly to the wily quote that Nabokov himself gives about the pronunciation of his name—“My New England ear is not offended by the long, elegant middle o of Nabokov as delivered in American academies. The awful ‘Na-bah-kov’ is a despicable gutterism.” Jack Kerouac, at the summit of a verbal mood swing, bursts into an old-timey Edward G. Robinson–chomping-on-a-cigar-butt cadence. He becomes earthily exuberant, reveling in a memory, and it is an entirely different exuberance than in his fiction. Max Frisch, the Swiss novelist, conducted his interview in German with an English translator despite being semifluent in English. He often gives an answer in German—easy, mellifluous German—then the translator will begin to translate into English, and Frisch, either dissatisfied with the translation or wanting to place special emphasis on an idea, will reenter in English with a different voice—halting, professorial, and unequivocal. He uses his bilingualism to play personae, to be as elusive as he is in his writing.

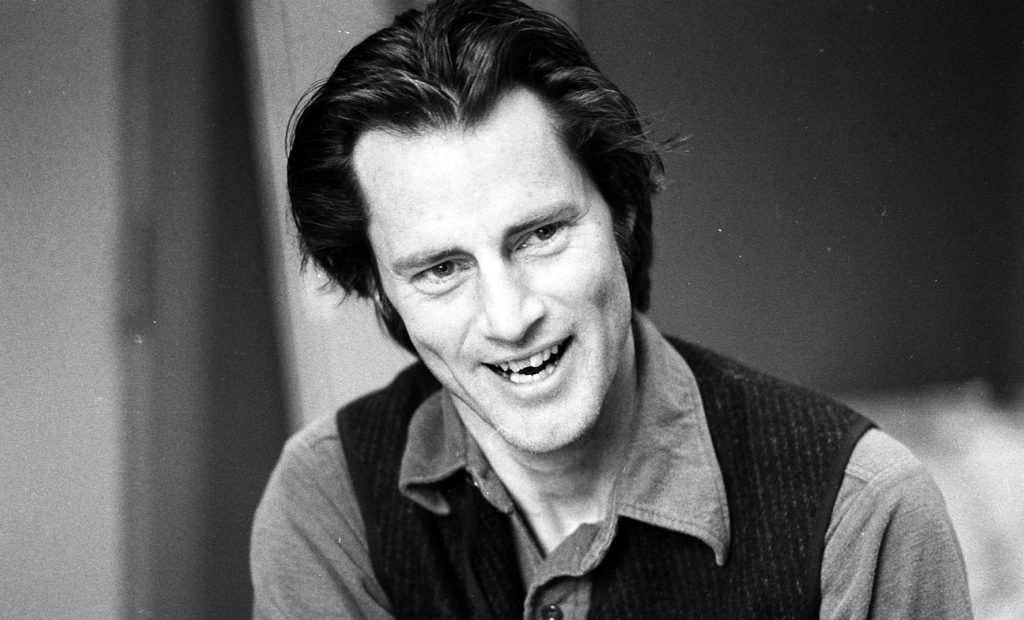

There is the way people laugh, always a revealing negotiation of control. Listening to Harold Bloom laugh—a sparkling helium cannonade—while discussing the noisy chair in The Death of Ivan Ilyich conveys more about his enthusiasm for literature than any sentence he could set to paper. It is not a polite, conversational laugh—it is a wave, a bodily wracking thing that arrests his words. Literature overcomes him. It is clear from the wildness of the laugh that Harold Bloom is comfortable with George Plimpton, his interviewer. Sam Shepard, giving an interview to Plimpton and two other editors at The Paris Review, whom he does not seem to know well, has a restrained sotto voce laugh that functions parenthetically to his speech. Salman Rushdie, conducting his interview before an audience at the 92nd Street Y, often seems to have composed complete, multiclause sentences in his head before answering, and when one of the internal punch lines draws a laugh from the crowd, he does not stop but plunges ahead insistently. He is lightly antagonistic to the audience—aware that he is being charming but standing at a distance to that charm.

There are the interruptions of incidental sound and the gravitational effect they have on the conversation. An ambulance wails through one of Jay McInerney’s answers, and his voice gets a little louder, his point just a little more strident. The phone rings in the middle of Sam Shepard’s interview, and Plimpton is heard asking the caller if he can call him back later, as he is in the middle of a “conference.” Shepard teases him lightly about calling the interview a conference, and the conversation flows more freely from that point forward. The tape clicks over in the middle of one of Don DeLillo’s answers, and the interviewer asks him to repeat his previous sentence in case the recorder cut it off. DeLillo does so without objection, but with a flatter, impatient affect—it sounds more like a line from one of his novels.

My favorite interview in the Morgan Library archives is one unconnected to The Paris Review and resistant to any transcription. In the seventies, George Plimpton interviewed a man named Pierre Etchebaster, born in France in 1893, for Pierre’s Book: The Game of Court Tennis. Etchebaster was a veteran of Verdun and considered one of the greatest-ever players of “real tennis,” so called at the time because it preceded “lawn tennis.” Just as it seems to me that people in the past had different faces, there are also voices that belong entirely to bygone eras. Pierre Etchebaster’s voice sounds like the original from which the stereotypical hacky French accent was cast. It is a valuable artifact in itself. Throughout the interview, Pierre is bouncy and cheerful, enthusiastically spelling out names when George cannot penetrate his accent, displaying an infectious delight in the alphabet itself. At one point, though, George asks Pierre about what it was like fighting at Verdun, where almost a million soldiers died in a battle that lasted an interminable nine months. Pierre releases an unclassifiable sound and exclaims, “Oh! I don’t want to make you sick!” The sound—something like a gasp, something like a shriek—carries meaning beyond language. It steps into the breach of words and narrative. These sounds throw an odd, expansive light onto the words on the page and have their own untranslatable glow, demanding its own understanding.

Stepping past the glass into the reading room, there is a moment in which the entire space is incarnated in sound and scent, in which the muffled scrape of a chair sliding over carpeting, the door handle warmed by other hands seem to achieve new dimensions. Soon the urgent newness of perception fades, and each element relaxes into its place. Soon there is the strangely comforting thought that there is always something else central and illuminating just beyond the fringes of our attention. The audio and the written interviews enrich each other while standing entirely on their own—our sense of the space simply deepens, and a new angle of sight presents itself.

No comments:

Post a Comment