California English (or Californian,

Californian English) is a

dialect of

the English language spoken in

California.

[1]California is

home to a

highly diverse population, which is

reflected in

the historical and continuing development of

CaliforniaEnglish.

History

English was first spoken on a

wide scale in

the area now known as

California following the influx of

English-speaking Whitesfrom the United States (and also Canada and Europe)

during the California Gold Rush.

The English-speaking populationgrew rapidly with further settlement, which included large populations from the Northeast,

South and the Midwest. Thedialects brought by

these pioneers were the basis for the development of

the modern language: a

mixture of

settlers from theMidwest and the Border South produced the rural dialect of

Northern California, whereas settlers from the Lower Midwestand the South, (especially Missouri and Texas),

produced the rural dialect of

Southern California.

Before World War I,

the variety of

speech types reflected the differing origins of

these early inhabitants. At

the time a

distinctly Southwestern drawl could be

heard in

Southern California. When a

collapse in

commodity prices followed WorldWar I,

many bankrupted Midwestern farmers migrated to

California from Nebraska, Ohio, Illinois, Minnesota, and Iowacontributing to a

new homogenized speech in

urban sprawl, where teachers banned "ain't," 'awl' in

favor of

oyill (oil),[2] and"I'll" in

favor of

ayill in

grammar schools. Subsequently, incoming groups with differing speech, such as

the speakers of

Highland Southern during the 1930s, have been absorbed within a

generation. The Dust bowl migration of

the so-calledOkies re-introduced a

purer Southwestern accent to

the West Coast in

the 1920s and 30s before the migration ended in

World War II.[citation needed]

California's status as a

relatively young state is

significant in

that it

has not had centuries for regional patterns to

emerge andgrow (compared to, say, some East Coast or

Southern dialects). Linguists who studied English as

spoken in

Californiabefore and in

the period immediately after World War II

tended to

find few if

any distinct patterns unique to

the region.[3]However, several decades later, with a

more settled population and continued immigration from all over the globe, a

noteworthy set of

emerging characteristics of

California English had begun to

attract notice by

linguists of

the late 20thcentury and on.

Phonology

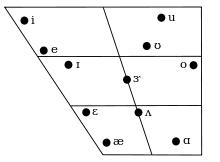

As a

variety of

American English,

California English is

similar to

most other forms of

American speech in

being a

rhotic accent,

which is

historically a

significant marker in

differentiating different English varieties. The following vowel diagramrepresents the relative positions of

the stressed monophthongs of

the accent, based on

nine speakers from southernCalifornia.[4] Notable is

the absence of

/ɔ/,

which has merged with /ɑ/ through the cot–caught merger, and the relativelyopen quality of

/ɪ/ due to

the California vowel shift discussed below.

Several phonological processes have been identified as

being particular to

California English. However, these shifts are byno

means universal in

Californian speech, and any single Californian's speech may only have some or

none of

the changesidentified below. The shifts might also be

found in

the speech of

people from areas outside of

California.

- Front vowels are raised before /ŋ/, so that /æ/ and /ɪ/ are raised to [e] and [i] before /ŋ/. This change makes forminimal pairs such as king and keen, both having the same vowel [i], differing from king [kɪŋ] in other varieties ofEnglish, though it is not spread evenly and the pronunciation [kɪŋ] still exists in many areas. Similarly, a word like rangwill often have the same vowel as rain in California English, not the same vowel as ran as in other varieties. This raisingis also found in the American Southeast.

- The vowels in words such as Mary, marry, merry are merged to [ɛ]. This merging is also found in southeast Englandand in the American Southeast.

- Most speakers do not distinguish between /ɔ/ and /ɑ/, characteristic of the cot–caught merger. A notable exceptionmay be found within the San Francisco Bay Area, many of whose inhabitants' speech somewhat reflects influence ofnew arrivals from the Northeast.

- According to a phonetician studying California English, Penelope Eckert, traditionally diphthongal vowels such as/oʊ/ as in boat and /eɪ/, as in bait, have acquired qualities much closer to monophthongs in speakers, similar to theAmerican Southeast.

- The pin–pen merger is complete in and around Kern County and northern Los Angeles County; speakers in Sacramentoeither perceive or produce the pairs /ɛn/ and /ɪn/ close to each other.[5]

- Speakers in the Greater Los Angeles area often quickly slur vowel sounds, making certain syllables sound longer andflow closer.[6]

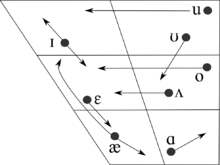

One topic that has begun to

receive much attention among scholars in

recent years has been the emergence of a

vowel shift unique to

California. Much like other vowel shifts occurring in

North America, such as

the Southern Shift,

NorthernCities Shift, and the Canadian Shift,

the California Vowel Shift is

noted for a

systematic chain shift of

several vowels.

This image on

the right illustrates the California vowel shift. The vowel spaceof

the image is a

cross-section (as if

looking at

the interior of a

mouth from a

side profile perspective); it is a

rough approximation of

the space in a

humanmouth where the tongue is

located in

articulating certain vowel sounds (theleft is

the front of

the mouth closer to

the teeth, the right side of

the chart beingthe back of

the mouth). As

with other vowel shifts, several vowels may be

seen moving in a

chain shift around the mouth. As

one vowel encroachesupon the space of

another, the adjacent vowel in

turn experiences a

movement in

order to

maximize phonemic differentiation.

Two phonemes, /ɪ/ and /æ/,

have allophones that are fairly widely spreadapart from each other: before /ŋ/,

/ɪ/ is

raised to

[i] and, as

mentionedabove, may even be

identified with the phoneme /i/. In

other contexts, /ɪ/has a

fairly open pronunciation, as

indicated in

the vowel chart above. /æ/ is

raised and diphthongized to

[eə] or

[ɪə] before nasal consonants (a

shiftreminiscent of, but more restricted than, non-phonemic æ-tensing in

theInland North); before /ŋ/ it

may be

identified with the phoneme /e/.

Elsewhere /æ/ is

lowered in

the direction of

[a].

The other parts of

the chainshift are apparently context-free: /ʊ/ is

moving towards [ʌ],

/ʌ/ towards[ɛ],

/ɛ/ toward [æ],

/ɑ/ toward [ɔ],

and /u/ and /oʊ/ are diphthongswhose nuclei are moving toward [i] and [e] respectively.[7]

Unlike some of

the other vowel shifts, however, the California Shift Theory would represent the earlier stages of

developmentas

compared to

the more widespread Northern Cities and Southern Shifts, although the new vowel characteristics of

theCalifornia Shift are increasingly found among younger speakers. As

with many vowel shifts, these significant changesoccurring in

the spoken language are rarely noticed by

average speakers; imitation of

peers and other sociolinguisticphenomena play a

large part in

determining the extent of

the vowel shift in a

particular speaker. For example, while somecharacteristics such as

the close central rounded vowel [ʉ] or

close back unrounded vowel [ɯ] for /u/ arewidespread in

Californian speech, the same high degree of

fronting for /oʊ/ is

common only within certain social groups.

The southern Central Valley (Kern, Tulare, and Kings Counties), is the last large rural (but not desert) region in SouthernCalifornia and maintains many of the original dialect distinctive of Southern California as a part of the American Southwest,including the pin-pen merger, a single phoneme in contrast to the nasal diphthong /ãɪ/ of the U.S. Northeast, respectable useof "ain't" and "yes ma'am." This is distinct from the fast-talking homogenized speech common to the very large cities of LosAngeles, the Bay Area, and in cities throughout English-speaking America.

Many rural white Californians speak with a

western Oklahoma-like drawl that is

quite distinct from the high-pitched, fast-talking of

city folk in

coastal Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay region. Currently, it is

often assumed that the CentralValley's holdout of

Southwestern speech and culture (such as

rodeos) was strengthened by

people from western Oklahomawho emigrated during the Dust Bowl. But no

documentation of

change of

the dialect before and after the arrival of

the "Okies"is

submitted. Rather, rural Southern California was already populated long before, by

descendants of

settlers who came to

California in

the Southwest from different regions of

the Southeast,[8] fully explaining the speech patterns of

rural SouthernCalifornia as

native and entrenched.

Lexical characteristics

The popular image of a

typical California speaker often conjures up

images of

the so-called Valley girls popularized by

the1982 hit song by

Frank and Moon Unit Zappa, or "

surfer-dude"

speech made famous by

movies such as

Fast Times at Ridgemont High.

While many phrases found in

these extreme versions of

California English from the 1980s may now be

considered passé, certain words such as

awesome,

totally,

fer sure,

harsh,

gnarly,

and dude have remained popular in

California and have spread to a

national, even international, level. The use of

the word like for numerous grammaticalfunctions or as

conversational "

filler"

(e.g. in

place of

thinking sounds "uh" and "um") has also remained popular in

CaliforniaEnglish and is

now found in

many other varieties of

English.

A

common example of a

Northern Californian[9] colloquialism is

hella (from "hell of a

(lot of)", rare euphemistic alternative,hecka) to

mean "many", "much", "so" or

"very".[10] It

can be

used with both count and mass nouns. For example: "I

haven'tseen you in

hella long"; "There were hella people there"; or

"This guacamole is

hella good." Pop culture references to

"hella"are common, as in

the song "

Hella Good" by

the band No

Doubt, which hails from Southern California, and "Hella" by

theband Skull Stomp, who come from Northern California.[11]

California, like other Southwestern states, has borrowed many words from Spanish,

especially for place names, food, andother cultural items, reflecting the heritage of

the Californios.

High concentrations of

various ethnic groups throughout thestate have contributed to

general familiarity with words describing (especially cultural) phenomena. For example, a

highconcentration of

Asian Americans from various cultural backgrounds, especially in

urban and suburban metropolitan areasin

California, has led to

the adoption of

words like hapa (itself originally a

Hawaiian borrowing of

English "half"[12]). A

personwho was hapa was either part European/Islander or

part Asian/Islander. Today it

refers to a

person of

mixed racial heritage—especially, but not limited to, half-Asian/half-European-Americans in

common California usage) and FOB ("fresh off theboat", often a

newly arrived Asian immigrant). Not surprisingly, the popularity of

cultural food items such as

Vietnamese phởand Taiwanese boba in

many areas has led to

the general adoption of

such words amongst many speakers.

In

1958, essayist Clifton Fadiman pointed out that Northern California is

the only place besides England where the wordchesterfield is

used as a

synonym for sofa or

couch.

[13]

Freeway nomenclature

Since the 1950s and 1960s, California culture (and thus its variety of English) has been significantly affected by "car culture,"that is, dependence on private automobile transportation and the effects thereof.

One difference between California and most of

the rest of

the United States has been the way California English speakersrefer to

highways, or

freeways. The term freeway itself was originally not used in

many areas outsideCalifornia;

[citation needed] for instance, in

New England,

the term highway is

universally used. Where most Americans mayrefer to "

I-80"

for the east-west Interstate Highway leading from San Francisco to

the suburbs of

Oakland or

"I-15" for thenorth-south artery linking San Diego through Salt Lake City to

the Canadian border, Californians—especially SouthernCalifornians—are less likely to

use the "I." Northern and Southern Californians alike are even less likely to

use the"interstate" designation in

naming freeways.[citation needed]

The numbering of

freeway exits, common in

most parts of

the United States,

has only recently been applied in

Californiaand initially appearing only in

more populous areas. Thus, virtually all Californians refer to

exits by

signage name rather thanby

number, as in

"the Grand Avenue exit" (in Los Angeles) rather than "Exit 21."

Californians sometimes refer to

the lanes of a

multi-lane divided highway by

number, "The Number 1

Lane" (also referred toas

"The Fast Lane") is

the lane farthest to

the left (not counting the carpool lane), with the lane numbers going up

sequentially to

the right until the far right lane,[14] which is

usually referred to as

"The Slow Lane." In

areas where three andoccasionally two lane freeways are more common, the lanes are simply the "fast lane," "middle lane" and "slow lane."

- Northern Californians will typically say "80," "I-80," "Business 80," or "101" ("one-oh-one") to refer to freeways. Somelong-time San Francisco Bay Area residents and many traffic report broadcasts still refer to such highways by nameand not number designation: "Bayshore" for Highway 101, or "the Nimitz" for I-880, the portion of the EastshoreFreeway which was named for Admiral Chester Nimitz, a prominent World War II hero with strong local ties. StateRoute 1 is called "Highway 1" or simply "One" (that is, "take One down the coast"). Differentiation among freeways isgenerally determined, by stating East to West, or North to South. Because the major freeways go either north to south(odd numbered, e.g. 101 or I-5) or east to west (even numbered, e.g. 74 or 80), it's only necessary to differentiatebetween those two directions, except for shorter, intrastate freeways.

- In the Greater Los Angeles area (Los Angeles County, Orange County, Ventura County, and the Inland Empire)and San Diego, freeways are referred to either by name or by route number (perhaps with a direction suffix), but withthe addition of the definite article "the," such as "the 405 North" or "the 605 (Freeway)". This is in contrast to typicalNorthern California usage, which omits the definite article.[15][16][17]

- There is no road named the "Los Angeles Freeway"; instead, each freeway which radiates from Downtown Los Angeles is named for its nominal terminus in some other city, such as Santa Monica, Pomona or San Bernardino.News reports will occasionally refer to the Santa Monica and Santa Ana freeways as such; however, residents willrarely refer to the 405 freeway as the San Diego Freeway (other than on street signs). The majority of natives stick tocalling the freeways by "The" + (Freeway number).[citation needed]

- Conversely, the older state highways are generally called not by their numbers but by their names, as used onsignage and in postal addresses. For example, in Southern California, State Route 1 is called the Pacific CoastHighway and is often referred to as "the PCH".[citation needed]

- The distribution of these contrasting nomenclatures is irregular, and indicate the extent of integration with the GreaterLos Angeles economic sphere of influence. Along Highway 101, the shift occurs at the Santa Ynez Mountains, sothat residents of Santa Barbara County and San Luis Obispo County speak of "the 101," but residents of thesouthernmost parts of Monterey County call the same freeway "101" (although some residents also say "the 101,"since there are both people from North and Southern California living there.) Along Interstate 5, this border is lessclear. Residents of Bakersfield, over the San Gabriel Mountains from Los Angeles, speak of "the Five" and "the 99",but this use is notably absent in Fresno. Towns in the Mojave Desert tend to use the "the" at least as far as Las Vegas; Las Vegas has notable historic ties to the Los Angeles area, given that as much as 25% of visitors to LasVegas are from Southern California. Residents of San Diego, the Imperial Valley, and Phoenix, Arizona[18][19] followSouthern California usage as well.

Urban geographical nomenclature

In referring to neighborhoods and districts within San Francisco or Los Angeles, residents' typical usage runs counter tofreeway nomenclature. In San Francisco one hears of the Mission, the Castro, or the Haight; but in Los Angeles, the article isomitted in similar contexts, for example Los Feliz, Sawtelle, and Pico Union.

Northern California

The metro region often referred to as

the Bay Area includes San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Alameda, Marin,Contra Costa, Sonoma, Solano and Napa counties.

The San Francisco Bay Area is commonly referred to as "the Bay Area" or sometimes simply as "The Bay". The Bay Area issub-divided into several regions:

- "The City" or simply "SF" refers to San Francisco proper.

- The "North Bay" encompasses Marin County, Napa County, Sonoma County and Solano County.[20]

- The "South Bay" encompasses the cities of the Santa Clara Valley, including San Jose, and can refer to all of Santa Clara County, as far south as Gilroy and sometimes Santa Cruz and San Benito counties. Mountain View, home ofGoogle, is undeniably part of Silicon Valley, but northwestern parts seem to be more integrated with Palo Alto.

- The "East Bay" extends inland from the eastern shores of the San Francisco Bay and includes Alameda and Contra Costa counties. East Bay cities include Oakland, Berkeley, Concord, Walnut Creek, Fremont, Richmond, San Ramon, Hayward, and San Leandro. Cities on the Bay side of the East Bay Hills are sometimes referred to as the"Near East Bay", and historically, inland cities along the I-680 corridor have been referred to as the "Far East Bay". Thedefinition of this term has been muddied in recent years as suburban sprawl from the Bay Area spilled into the CentralValley, adding a distinct third subregion to the East Bay.

- "The Peninsula" refers to the San Francisco Peninsula south of the City of San Francisco, encompassing the cities inSan Mateo County, including Daly City, San Mateo, Redwood City and Menlo Park, as well as Palo Alto (in SantaClara County). It is virtually never referred to as the "West Bay". Palo Alto is considered "on the Peninsula", which despitebeing in Santa Clara County has long historical ties with the Peninsula (especially with Menlo Park); for example, JaneLathrop Stanford kept a personal waiting room at the Menlo Park train station, despite the Stanford estate's proximity toPalo Alto.

- "Oakland" is often called "Oaktown" by its African American residents, colloquially. The sobriquet also is found as part ofsmall local merchandise and service businesses. The popular rise of medical marijuana cultivation and marketingspawned the introduction of "Oaksterdam", a portmanteau of Oakland and Amsterdam. (If Oakland had been named,like San Francisco and San Jose, according to its Spanish name, it would have been called Las Encinas [ The Oaks ].)

The term "Frisco" is

rarely used by

San Francisco Bay Area residents, much as

"The Big Apple" is

not typically used by

native New Yorkers.

However, though well-known newspaper columnist Herb Caen once harshly criticized the use of

theterm "Frisco," he

later recanted, and the term continues to be

used.[21] Still, the term "Frisco" continues to be

viewed by

many as

either revealing ignorance, or as

vaguely derogatory. Emperor Norton, a

colorful 19th century inhabitant of

SanFrancisco, once issued a

proclamation about the City's nickname:

| “ | Whoever after due and proper warning shall be heard to utter the abominable word "Frisco", which has nolinguistic or other warrant, shall be deemed guilty of a High Misdemeanor, and shall pay into the ImperialTreasury as penalty the sum of twenty-five dollars.[22] | ” |

In

1918 in

his courtroom, a

San Francisco judge rebuked a

Los Angeles resident's use of

the nickname "Frisco" by

saying"No one refers to

San Francisco by

that title except people from Los Angeles."[23] Decades later, San Francisco columnistHerb Caen renewed the drive to

keep "Frisco" out of

San Francisco.[24]

Herb Caen pointed out in his column that some residents of Los Angeles refer to San Francisco as "Toytown".

Santa Rosa,

north of

San Francisco, is

sometimes referred to as

"Rosa" or

"SR".

Some Northern Californians refer to Sacramento, the state capital, as "Sac", "Sacto", "Sactown", "Smacktown","Sacmenistan", "Swagramento", "Sacra" (by the Chicano community), "Sacratomato" (for the local tomato canning industry)and various other nicknames.

Bay Area and Sacramento residents speak of

going "up the hill" into the neighboring mountains to

Lake Tahoe or

Reno, Nevada,

but "over the hill" for crossing the Santa Cruz Mountains,

either to

Santa Cruz or

Half Moon Bay. By

the sametoken, those living in

the Foothills will speak of

going "down the hill" when traveling into the Sacramento area. In

theSacramento area, "the Valley" refers to

the Central Valley. Also residents of

West Marin will call the San Geronimo Valley as

"the valley" and Mount Tamalpais "the hill", as in

you're from "the valley" or

I'm going "over the hill". Additionally, residents of

the Bay Area will sometimes refer to

the area of

the Santa Clara Valley and surrounding cities as

"the Valley" or as

the morefamous term, "

Silicon Valley".

Residents of

Santa Cruz use the phrase "over the hill" to

refer to

Silicon Valley (which is

oftenreferred to by

Santa Cruz "locals" as

"The Pit"), but for them "the Bay" refers to

closer Monterey Bay,

not San Francisco Bay.

Southern California

Southern California has many distinctive accents and dialects; these often reflect the geographic origins of

the people whocame there. Bakersfield English and the "Valley Girl" dialect of

the San Fernando Valley have their roots in

the OzarkEnglish of

Arkansas and Missouri, and first developed when many people from the Ozarks migrated to

California in

the1930s. East Los Angeles and the Gateway Cities house a

distinctive form of

Chicano English.

These dialects can exist in

very small areas, such as

the traditionally New Orleanian Yat in

northern Pasadena.

In

the city of

Los Angeles, the terms "Westside" and "Eastside" are frequently used to

refer to

regions on

either side of

thecity. The boundaries of

these regions are not defined, and whether certain neighborhoods should be

included in

theWestside or

the Eastside remains a

heated topic of

discussion.[25] Generally, the Westside includes neighborhoods with thearea code 310, including Santa Monica, Westwood and Beverly Hills.

The Eastside includes neighborhoods east of

theLos Angeles River such as

Boyle Heights,

East Los Angeles and Whittier.

Neighborhoods south of

downtown Los Angeles are typically referred to as

"South Central" (though officially renamed to"

South L.A."

2003). South Central initially referred to

Central Ave South of

Jefferson which was a

major location for jazz andnightlife in

the fifties and sixties. Neighborhoods in

South L.A. include Watts,

Leimert Park,

and Inglewood.

The San Fernando Valley,

which lies north of

the Santa Monica mountains, is

often called simply "the Valley." It

became a

cultural phenomenon and a

major real estate destination for millions of

Angelenos to

call home in

the 20th century, andindeed where the "Valley girl/boy" accent developed in

the later 1970s and 1980s or

early 1990s become popularized by

teenagers and young adults nationwide and globally through Hollywood's media circuit.[citation needed]

Residents of

Long Beach simply refer to

their city as

Long Beach. Residents outside the region may refer to

the city as

the"LBC," popularized in

the media by

famous residents, such as

the rapper Snoop Dogg and the ska punk band Sublime.

The Inland Empire,

which encompasses cities in

San Bernardino, Riverside, and sometimes the eastern edge of

LosAngeles counties, is

commonly referred to as

"the I.E." or

"the 909"

for its original telephone area code. Although the United States Census Bureau defines the Inland Empire region as

all of

San Bernardino and Riverside counties, these counties'high or

low desert regions are frequently excluded from the colloquial definition, which refers instead to

the more urbanizedarea around the cities of

Riverside and San Bernardino and other cities in

the Pomona Valley which may also include LosAngeles County. Typically, this excludes all areas north of

Cajon Pass and San Gorgonio Pass.

Residents in

communities in

the San Gabriel and San Bernardino Mountains (i.e. Crestline,

Wrightwood,

Lake Arrowhead,

Big Bear)

will refer to

people on

either side of

the mountains as

"flat-landers". This practice is

also commonamong hikers and outdoor enthusiasts when referring to

those who do

not venture into the mountains. In an

example of

wryunderstatement, the residents of

these mountain communities also refer to

the rather lengthy journeys between them and thesurrounding lowlands as

"going down (or up) the hill."

A

common colloquialism for Orange County is

"behind The Orange Curtain",

referring to

the politically conservativedemographics for that area. This term is

typically used by

Californians who self-identify as

politically liberal. According to

theFox television show The O.C.,

the abbreviation of

the county's name tends to be

mainly used by

those from outside of

thearea, rather than natives. Many residents of

Orange County refer to

their telephone area codes to

describe where in

OrangeCounty they are from. The "562" or

"714" refers to

people in

Northern Orange County and the older suburban communitiesof

Anaheim,

Brea,

Buena Park,

Cypress,

Fountain Valley,

Fullerton,

Garden Grove,

Huntington Beach,

La Palma,

Los Alamitos,

Orange,

Santa Ana,

Seal Beach,

Sunset Beach,

Tustin and Westminster,

while "949" refers to

more affluentand recently developed communities in

South Orange County such as

Aliso Viejo,

Coto de Caza,

Foothill Ranch, Irvine,

Laguna Hills,

Mission Viejo,

Newport Beach,

and Rancho Santa Margarita, .

The "909" area code refers to

people inlandfrom Orange County, typically from Riverside and further inland, and is

used by

many native southern Californians,especially those living in

cities near the beaches, as a

derogatory term for tourists, "909ers". Rarely, people will even refer to

their zip codes to

communicate where they live, many times an

indication of

their income level.

In

San Diego County,

"South Bay" refers to

the area adjacent to

the southern portion of

San Diego Bay. Suburbs in

thenorthern half of

the county almost always identify as

simply North County and suburbs immediately east of

the city proper,though geographically still located in

the western half of

the county, identify similarly as

East County. San Diego residents willalso sometimes define their location relative to

major highways. "South of

the 8"

refers to

communities south of

the I-8, whichcuts roughly through the City of

San Diego. This term also implies a

socioeconomic divide, residents and communities areperceived as

being less affluent, as

well as a

greater concentration of

ethnic minorities. Anothe

r common example is "East ofthe 5", in which many central beach community residents will use to define where in San Diego they will not go to. As the I-5follows the coastline in much of San Diego, this is a way of signifying an inclination to stay within the coastal regions of SanDiego. Alternatively, "east of the tracks" refers to primarily the same inland areas, as the main Amtrak Pacific Surfliner trainroute runs along a path similar to that of the I-5 between Orange County and its terminus at Union Station, also known as theSanta Fe Depot, near downtown San Diego. "West of the tracks" refers to the part of the beach communities nearest to theocean.

And finally the California Desert region: the Coachella Valley and Imperial Valley are referred to as

the "Desert", but a

more"Southwestern" cultural emphasis on

desert western living imparts a

more Hispanic and American Indian flavor to

the localdialect. The Mojave Desert and Mono Lake area is

also known as

the "High Desert" due to

the region's higher elevations,but has a

more rural American (i.e. Southern, Midwest/Central and Texan/Western) cultural character.[citation needed]

Location Pronunciation

Due to influence from the Spanish language, most city and street names are pronounced close to how they would in theirnative language if not identically.

Examples

- San Jose- typically pronounced "san oh-ZAY" or "san hoh-ZAY"; the pronunciation "sanna-ZAY" is discouraged

- Los Gatos- typically pronounced "los GAT-oce" or "los GATT-oce", sometimes "loss GATT-oce"; the pronunciation "lissGATT-iss" is discouraged

Exceptions

- Vallejo- original Spanish "va-YAY-ho"; English "vuh-LAY-oh"

- Los Angeles- original Spanish "loce AWN-hay-lace"; English "loss AN-juh-liss"

- Junipero Serra- original Spanish "hoo-NEE-per-oh SEH-rrah; English "you-NIP-er-oh sair uh"

- El Camino Real- original Spanish "ell-kah-ME-no rray-AHL"; English "ell-kah-ME-no REE-ahl"

No comments:

Post a Comment