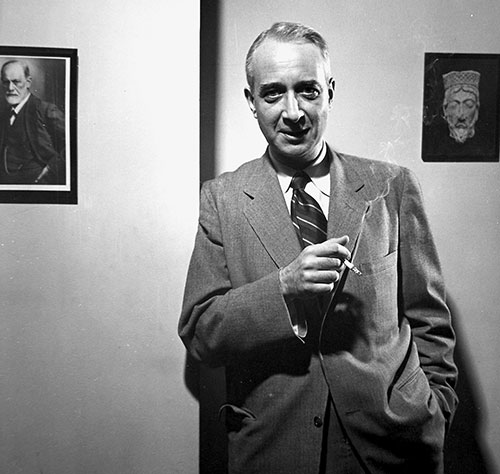

Lionel Trilling was a dominant figure in American literary criticism in the middle decades of the last century, and Adam Kirsch’s judicious selection of his letters throws instructive light on both Trilling’s life and American intellectual culture from the 1920s to the 1970s. For anyone concerned with the many leading writers, critics, and thinkers with whom Trilling corresponded or curious about how the son of Jewish immigrants came to play such a central role in American literary life, it is a fascinating book.

Trilling’s parents were by no means the Yiddish-speaking types one associates with the Eastern European immigrants of this period. His mother had actually grown up in England, and his father spoke perfectly correct English without a foreign accent. It is noteworthy that his parents would not consider sending him to City College, where so many children of the immigrant generation were educated, because they thought it was beneath him. Instead, they directed him to Columbia, the institution at which, after temporary teaching stints in Wisconsin and at Hunter College, he would spend his entire academic career. Trilling’s affinity for British high culture was not surprising.

There were three great points of departure in Trilling’s intellectual development, two of which he left entirely behind early on and a third that remained with him to the end: a somewhat vague and wholly secular Judaism, Marxism, and Freudianism. His consistent disengagement from all expressions of Jewish identity is a complicated issue to which I shall return. He and his wife Diana had a flirtation with Marxism in the early 1930s, as did so many New York intellectuals then, but they never joined the Communist Party, and he was soon horrified by the brutality of Stalinism and became a staunch anti-Marxist. In a contentious letter to the theater scholar Eric Bentley in 1946, he writes, “I live in deep fear of Stalinism” and goes on to observe aptly that in one respect Stalinism was more pernicious than Fascism because “it has taken all the great hopes and all the great slogans [and] has recruited the people who have shared my background and culture and corrupted them.” On Freud, he wrote a number of finely reflective pieces through to late in his life, and this intellectual interest was no doubt strongly reinforced by the fact that both he and Diana underwent psychoanalytic treatment for decades.

The two of them were highly neurotic—a term Trilling does not hesitate to apply to himself in his letters—although their neuroses were quite different. There are some indications in Trilling’s letters of corrosive self-doubt and of black moods that have the distinct look of depression. Diana, a critic and journalist Trilling sometimes chose to regard as his equal although she was not, was subject to panic attacks and was so hampered by phobias that she could not bring herself to enter an elevator, requiring the couple to live in a ground-floor apartment. Her grasp of factual matters was sometimes a little shaky, as I had occasion to personally learn. In 1978 I wrote an article on the critic Alfred Kazin in which I referred to Trilling, essentially defending him against Kazin. Although Kazin irritably imagined that I was a disciple of Trilling in his later-published journal, Diana saw my article as an attack on her husband. She then somehow picked up the notion that I was the son of the Polish Bundist leader Viktor Alter and hence hostile to Lionel because of his anti-Marxism. In fact, my father came from Romania and had no connection whatever with the Bund.

A somewhat unexpected aspect of the Trilling marriage emerges from these letters. The early phase of their relationship was intensely passionate and evidently involved keen sexual excitement, at least on his side. Trilling regularly addresses Diana in his letters as “Dearest” or “Beloved” and says she is the most extraordinary thing that has ever happened to him. In one letter, he even tells her everything he longs to do with her body in four-letter detail. Such things, alas, rarely last, and in the course of time sexual problems, according to the report of their intimates, emerged, along with occasional outbursts of vituperative rage by Lionel that compelled Diana to flee the room. But this was a marriage, whatever storms may have roiled it, that was made to last. Nearly a quarter of a century after they met, when Trilling was traveling abroad for the first time—to England, of course—he was still addressing Diana in his letters as “Dearest” and writing her with companionable kindness and consideration. To the end, he remained loyal to her, invariably praising or defending her writing in his letters to literary friends.

Trilling of course became famous primarily as a literary critic, and at the peak of his career he was read, one might say, religiously by most of the New York intelligentsia, as well as by many others elsewhere. One wag remarked at the time that young couples in these circles followed every Trilling essay the way good Anglicans read their pastor’s weekly sermon. Trilling’s own feeling about his work as a critic, the letters often show, was not of a piece with adulation it inspired.

He did not actually care to be a critic, he remarks several times in his letters, or to be thought of as one. (One must note, nevertheless, that he responded with alacrity to invitations to write critical essays and reviews; in the last year of his life he was working on an essay on Jane Austen.) He eagerly embraced a comment in a letter from the French philosopher Étienne Gilson that “he wasn’t really a literary critic,” although we are not told what Gilson imagined him to be. I would tentatively describe Trilling as a moral observer of society, culture, and politics, perhaps even a kind of improvisatory social theorist. He was not much interested in engaging the specificities of literary works, however intelligently he may have read them. In a letter to his editor Pascal Covici, he remarks of The Liberal Imagination, his most famous book, that “these essays, although essays chiefly in literature, all point beyond literature, to what we call life itself.”

His characteristic mode of discourse works through generalizations about society, prevalent attitudes and values, and much else, and one can often see this disposition in the letters. It is both a powerful resource and a limitation. Writing to Norman Podhoretz, he observes, “Very true that sex has been corrupted by the will, very true that sex, by being made extravagantly conscious, has become scientized and mechanized.” This is surely an interesting notion, but how could anyone know whether it is very true, or even true at all?

Trilling expresses a sense of camaraderie in writing to Edmund Wilson, noting that neither of them belongs to a school or trend or espouses a particular methodology: “Pleasant to think that someday an examination question will read: Name and discuss two general American critics who are not New Critics but are not Old Critics either.” He begins another letter to Wilson by invoking a famous phrase from Baudelaire, “mon semblable, mon frère.” Years later, however, writing to a critic who had just published a piece that discussed Wilson, he asserts of Wilson’s work, “I find it lacking in depth and breadth, and energy.” This strikes me as unjust, but I would hasten to say that what characterizes a good many of Trilling’s letters is a gnawing sense of dissatisfaction with everything that passes for criticism. Thus, he tells Isaiah Berlin, “I have become impatient with criticism in general and find it harder and harder to read it.” At several points, he says much the same thing about contemporary literature and art. A similar dissatisfaction is present in many of his comments about the academic world, his colleagues, and all but a few of his students. My own experience as his student was that, even while offering subtle insights, he tended to be casual to a fault in the classroom and a bit disorganized. He seemed to want to be somewhere else, doing something else.

Above all, that something else was writing fiction, not criticism. His first publications, when he was in his early twenties, were short stories and a few articles and reviews that appeared in The Menorah Journal, a distinguished intellectual periodical launched in 1915. (Its brilliant managing editor, Elliot Cohen, would become the founding editor of Commentarymagazine.)

He published just one novel, The Middle of the Journey (1947), whose principal character was based on Whittaker Chambers, an acquaintance of Trilling’s at Columbia College who would later be exposed as a Soviet spy. The novel is thoughtful and nuanced but rather pallid, a judgment with which he himself came to concur. In a 1972 letter he confesses, “I prevailed on myself to read part of it, and found it not bad, although not what I would want a novel of mine to be.” He repeatedly affirms in his letters the intention to produce a new novel, but it remained incomplete at the time of his death (it was published by Columbia University Press in 2008 as The Journey Abandoned: The Unfinished Novel).

Revealingly, in a letter aptly celebrating the achievement of Saul Bellow’s The Adventures of Augie March (he would later have problems with Bellow), he speaks of the “gift” it manifests “to see life everywhere” and notes that “the prose is really wonderful in its vivacity and energy.” These qualities are precisely what is absent from The Middle of the Journey, and one wonders whether Trilling, with all of his inhibitions and inner conflicts, would ever have been capable as a novelist of the spontaneous surrender to the momentum of his imagination. His wife says something to the same effect in her autobiography, couching the point in orthodox Freudian terms.

The Menorah Journal, initiated in a Jewish student organization of that era, may seem an unlikely launching pad for the career of the critic who would become an expositor of such figures as Matthew Arnold, E. M. Forster, and Wordsworth. This ostensibly paradoxical beginning points to the general question of Trilling’s identity as a Jew in his trajectory to prominence as an American man of letters. Trilling describes his parents as “Orthodox,” although this entailed little more than a kosher kitchen and the lighting of candles Friday night, as Diana confirms. The rabbi who prepared him for his bar mitzvah was Max Kadushin, who would much later write a book called The Rabbinic Mind on the “normal mysticism” of the ancient rabbis. Trilling read it and was impressed. It helped him to revise the one, rather curious, essay in which he discusses Judaism, “Wordsworth and the Rabbis.” Trilling proposes an analogy between the relation of the early rabbis to the Torah, as formulated by Kadushin, and Wordsworth’s relation to nature. This episode apart, what is clear in any case from Trilling’s letters is that growing up he was given barely any Jewish instruction beyond the ability to chant his haftarah by rote. The occasional comments he makes on Judaism and Jewish culture betray a total ignorance of their contents, and in a diatribe—a mode of expression quite uncharacteristic of him but a label entirely justified here—about Jewish sexual attitudes, he even refers to the ritual bath pious Jewish women go to after menstruating as “the mitzvah.”

Trilling had briefly seen in the intellectual community around The Menorah Journal the possibility of a new secular Jewish culture that would suit his sense of life. Writing to Elliot Cohen in 1929—he was 24 at the time—he speaks of the aspiration “to construct a society that can consider its own life from a calm, intelligent, dignified point of view; take delight in its own arts, its own thoughts, the vagaries of its own being.” Earlier in the same letter, he tells Cohen that he found he preferred his Jewish friends to his Gentile friends but that otherwise he “was not rebelling . . . merely ignoring” Judaism. He goes on to say that, “Implicit in my feeling about Judaism was that it was not unpoetic, but quite empty of meaning now and inclined to manifest itself stupidly.”

Within a few years, he would put the cultural project of The Menorah Journal well behind him. After the publication of his book on Matthew Arnold in 1939, he was promoted to tenure in the Columbia English department through the edict of Nicholas Murray Butler, the imperious, longtime president of the university, who was motivated by his admiration of the book. In this period, departments of English were bastions of genteel anti-Semitism. Trilling was the first Jew to become a permanent member of the Columbia department and would remain the only one for many years. The chairman of the department, Emery Neff, came to see Trilling in his apartment (in itself a remarkable step) after the promotion was imposed by Butler. According to Diana, he told Trilling that he was glad to have him aboard but that he hoped he would not use his presence as a wedge to bring in others of his race.

Trilling nowhere expresses any discomfort with this fraught situation in these letters, and in several letters he asserts that he had never suffered from anti-Semitism. For all his Anglophilia, he was not what used to be called a facsimile WASP. He never made the slightest gesture to hide his Jewish origins, but they remained just that, origins, with only the most tenuous relevance to his mature identity. There is certainly something honorable in his stance as a Jew by extraction only. While a graduate student, he declined an invitation to join the Columbia Club because he had learned from a close friend that “the club usually does not take Jews” and hence, “Under such a circumstance, you will surely perceive, I cannot decently stand for membership.” Understandably, he could not adopt this position a decade later when offered membership in an even more exclusive Columbia club, the English department, because his livelihood—quite precarious at this juncture—and his future career depended on his joining.

In a 1961 letter to Clement Greenberg, the eminent art critic and an editor at Commentary from 1945 to 1957, he recalls a bitter argument they had back in 1945 in which Greenberg accused him of Jewish self-hatred. At least according to Trilling’s recollection, he was on the point of starting a fistfight with Greenberg because of the accusation. In fact, Trilling’s letters show no real evidence of self-hatred but only a continuing ambivalence, a desire not to be chiefly identified as a Jew, as well as a few moments of vestigial respect for remembered familial values. When he learned of his mother’s death in 1964 while he was staying at Oxford, he accepted a prompt from Diana that it would be appropriate for him to recite the Kaddish at least once, and, after consulting Isaiah Berlin, he attended a Jewish student service and was surprised to find it “an affecting occasion and helpful in a way that I would not have expected.”

Many people, of course, behave differently at such moments than in everyday life, and Trilling’s usual predisposition was to preserve a certain cautious distance from Judaism or any sort of Jewish collective expression. In 1945, when Commentary was founded, Elliot Cohen invited him to become a contributing editor. Trilling firmly declined, explaining to his old friend that, “A great many intellectual problems and projects . . . have recently begun presenting themselves to me . . . and when I get around to handling them I do not want to do so in the character of a ‘Jewish writer’ or a ‘Jewish publicist,’ which would be, in some part, my identification if my name were on your masthead.” Trilling did from time to time contribute articles to Commentary, and his initial personal connection with the journal through Cohen would continue in another guise when his former student Norman Podhoretz assumed the editorship in 1960. But his resistance to any association with Jewish organizations and activities persisted. In 1959, when asked by the chaplain of the Seixas Society, Columbia’s Jewish student organization, to address the group, he first says, perhaps quite reasonably, that he has nothing of interest to say on Jewish cultural topics, and then adds, in an impeccably discreet formulation, referring to Jewish tradition, “My own relation to it is private and personal and not susceptible of discussion on a public occasion.”

Again, this seems perfectly honorable, given who Trilling was, but the disavowal of connection was accompanied by a sweeping dismissal of virtually all manifestations of Jewish culture, grounded in a nearly total ignorance of what those might be. Here is a ringing statement he makes in the course of still another refusal, in this case to cosign a report recommending the creation of what would become Brandeis University: “I know many Jews of large mind and morality, but I do not know a single mind in Jewish life that speaks as a Jew and with any intellectual authority in the exposition of Jewish values.”

Trilling had said much the same thing three years earlier in a symposium in the pages of the Contemporary Jewish Record, which was a kind of forerunner to Commentary. A group of intellectuals under 40 had been asked to speak to the question of American literature and the younger generation of American Jews. The symposiasts included such rising cultural stars as Delmore Schwartz, Isaac Rosenfeld, and Alfred Kazin. Trilling’s contribution was perhaps the bleakest. He concluded it by declaring, “I know of no writers who have used their Jewish experience as the subject of excellent work.” It seems he had not read, among other things, Henry Roth’s Call It Sleep (1934).

In 1938, just six years before the contribution to “Under Forty,” Gershom Scholem had come to New York to deliver the lectures that became Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism, one of the masterworks of intellectual history written in the 20th century, but Trilling, unsurprisingly, seems entirely unaware of it. It was simply not a direction in which he was looking from the safe haven of Hamilton Hall, where the Columbia English department was housed. In 1957, Scholem returned to New York to read sections of his magisterial biography of Shabbtai Zevi, then about to be published in Hebrew. I was a senior at Columbia College and came to his readings on campus. Many of the luminaries of the New York intelligentsia, including such friends of Trilling as Hannah Arendt and Meyer Schapiro, were there, but he did not appear.

There were a good many other things going on in Jewish culture during these years about most of which, admittedly, Trilling could not have known. In 1945 S. Y. Agnon published in Hebrew Only Yesterday, one of the century’s most original modernist novels. In New York, Jacob Glatstein was producing great poetry in Yiddish. I. B. Singer was writing remarkable fiction in Yiddish, which would begin to surface in English translation during the 1950s, the first notable appearance being Saul Bellow’s vigorous translation of “Gimpel the Fool” in, of all places, one of Trilling’s literary home bases, Partisan Review.

In this connection, I am led to ponder the attitude toward Irving Howe reflected in these letters, which, in the few mentions, is clearly dismissive or negative. Howe was part of the same Partisan Review and Commentary circle as Trilling. Like Trilling, he was neither a New Critic nor an Old Critic, and he, too, wrote for a general intellectual audience. But the two were in many ways antithetical.

Where Trilling wrote carefully measured, always sober prose, Howe inclined toward what he characterized in his celebrated 1969 essay, “The New York Intellectuals,” as “the style of brilliance,” which was lively, evocative, a bit showy, and sometimes wittily inventive. Howe’s critical range went beyond America and England to Europe and, in his later years, to Israel as well, and he was more disposed to engage with the work of individual living writers than to frame broad statements about the moral tenor of society. Whether his evolution from an early involvement in Trotskyism to democratic socialism rather than centrist liberalism bothered Trilling is unclear. But in midcareer, Howe also made a notable turn to Yiddish literature, which amounted to a return to his roots because he had grown up in a Yiddish-speaking home. I suspect that Trilling would have viewed Howe’s interest in Yiddish with puzzlement, if not skepticism. Why would the author of books on Hardy, Faulkner, and the political novel focus on the writers of a dying language, incapable as they must have been of speaking “with any intellectual authority”?

There is a dark side to Trilling’s dismissal of Jewish culture. In his diatribe on sexuality and the Jews—in the course of which, incidentally, he takes issue with Howe—he denounces Jewish “superstition,” “the compulsiveness and fear” of the Jews in regard to sex, and declares without qualification that “the antisexual impulse of East European Jews is extreme. . . . They think sex is dirty, that all the body is dirty.” Instructively, he goes on from this excoriation to one of his more withering condemnations of Jewish culture in general: “I find I grow less and less sympathetic with all manifestations of the culture. (And the late secular culture is erroneously overrated.) Nor do I like the culture any better in its attenuated American forms. I think it has injured all of us dreadfully.” These words were written toward the end of the decade when Bellow, Malamud, and then Philip Roth were coming into prominence. Trilling had in fact expressed keen admiration for Malamud’s story “The Magic Barrel,” but perhaps he thought it bore no relation to Jewish culture.

The “us” in the sentence just quoted, coupled as it is with the reference to being injured, is a usage that should give one pause. Is he speaking autobiographically or culturally? Is he in some way attributing his psychological struggles and in particular any sexual problems he may have had to growing up in a Jewish home? Such questions are, of course, speculative, but what does emerge from this and related passages in Trilling’s correspondence is that his assimilation into the loftiest spheres of American and British culture may not have been as perfect or as effortless as it sometimes seemed.

Trilling was surely comfortable in the world of Arnold and Ruskin and Wordsworth and with the exquisitely civilized discourse in which it was enshrined, but he appears to have nursed the grievance that his Jewish origins had wounded him—and were bound to wound anyone. Becoming an authority on literary and intellectual life in the English language entailed for him an absolute rejection of the alternative of Jewish culture. At its worst, he saw it as a black hole, the very opposite of an authentic culture and incapable in any way of sustaining the life of the mind and the spirit. Being for so long the sole English department Jew could not have been quite so easy as he claimed.

Trilling was a remarkably discerning, at times brilliant, essayist who threw subtle light on contemporary culture and its antecedents and on the internal contradictions of political loyalties, liberalism first among them. These intellectual virtues clearly justified the admiration his work elicited. He was also, according to the testimony of his familiars, an urbane and charming social presence, a quality that is also present in many of these letters. Yet he never entirely escaped his inner demons, and a good many of them seem to have been Jewish.

No comments:

Post a Comment