‘Girl With a Purell Earring’: How artists are tweaking famous paintings for our coronavirus era

April 11, 2020 at 5:00 a.m. CDT

Once Director considered where to jokingly flaunt her valued goo, it was lobe at first sight. On March 1, she tweeted a photo of herself with the bottle hanging from her ear. Then she was struck by the pun: “I’m the ‘Girl With a Purell Earring.’” On March 6, she tweeted her tweaked version of the famous Johannes Vermeer painting; the image was shared on Twitter by Peter Webber, director of the Oscar-nominated 2004 film “Girl With a Pearl Earring.”

Director’s tweet has been part of a wave of visual humor in the time of the coronavirus, as professionals and amateurs alike employ iconic fine art to respond to the realities and absurdities of pandemic life.

Vermeer to da Vinci. Michelangelo to Frida Kahlo. And often, that master of loneliness, Edward Hopper. Art meme-ing has long been with us, but some mix of quarantine creativity, idle isolation and the need to connect through humor in these uncertain times is sparking a stream of mischievous art alterations.

We are so accustomed to seeing the look of pain in Edvard Munch’s 1893 painting “The Scream” that Hrag Vartanian, editor in chief of the Brooklyn-based art site Hyperallergic, decided to jolt us by digitally removing the character completely — with the reason for the absence being left open to interpretation.

“I think photoshopping well-known works is quite soothing,” says Vartanian, who also is an artist. They are “images we’ve seen all our lives and often give us a sense of stability — so imagining them altered by the reality around us is comforting.”

As “The Scream” has been altered in recent weeks, some commenters on social media have noted that the central figure is touching the face — suddenly a no-no in these contagious times. Yet Vartanian chose to erase the figure for reasons of history and psychology.

“It reflects modern anxieties so well,” Vartanian says, “and particularly now that we know the sky's swirl of color was impacted by the 1883 volcano eruption in Southeast Asia, which had an impact as far away as Norway. The local — no matter if it's a virus or natural disaster — is often global.”

Vartanian wanted to highlight, too, that the screaming figure is not alone in the frame. “I wanted to create something jarring that reminds us to look at familiar things in new ways, just like we’re doing with our lives in the era of social distancing,” he says. “Everything right now is both familiar and strange.”

Hyperallergic also featured images edited by Valentina Di Liscia, who altered the Kahlo painting “My Two Fridas” to reflect social distancing. “I think this hopefully speaks to the potential for art to be inclusive — even when the art world sometimes isn’t,” Di Liscia says.

“That inside-joke feeling of, ‘Wow! That speaks to me!’ that you get from a meme is heightened when its contents also draw from our collective visual archive,” she says. “I hope the preponderance of art memes means more of us are allowing ourselves the freedom to play, interpret and even critique that archive.”

Stephanie Stebich, director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, says: “What I love about these memes is that they bring the highbrow of the art world into the lowbrow of the current. It’s about making these works more relevant to today."

Last month, Til Kolare, a digital artist and music producer in Leipzig, Germany, first played with “The Creation of Adam” section of the Sistine Chapel ceiling fresco. “I was thinking of the two hands of Michelangelo that were too close together,” he says, referring to God and Adam.

That begot his Instagram series, which includes spoofs of Hopper’s “Nighthawks” (with the famous diner now desolate); Renoir’s “Pont Neuf, Paris” (the city’s oldest bridge now uninhabited); Diego Velázquez’s “Las Meninas” (with the young Margaret Theresa of Spain now safely away from her doting entourage); and Leonardo da Vinci’s “Last Supper” (with Jesus isolated at the table). Kolare is now collaborating with a Leipzig museum to alter other paintings.

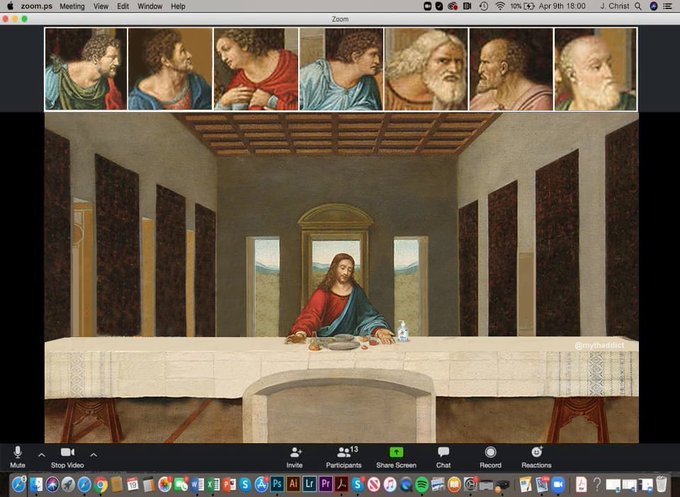

Another popular da Vinci alteration, tweeted last month by the account MythAddict, depicts the disciples conducting the Last Supper via Zoom meeting, inspired by images of the newly popular video-chat app. MythAddict, who in his creative life prefers to be known only as Cormac, is an artist in western Ireland. He was thinking of how Easter is a time of reunion, but this year “it is an impossibility for many to reconnect due to covid-19,” he says — even his Easter celebration with his own parents will be virtual.

In a “stay at home” era, Noah Regan looked close to home for inspiration. The cartoonist for the Waterloo-Cedar Falls Courier was solo-exercising in his house in early March when inspiration struck. He decided to adapt a work by fellow Iowa artist Grant Wood: his 1930 painting “American Gothic.” In Regan’s popular cartoon, the rural daughter wears a mask, safely distanced from her father.

“When things are predictable, that’s when we seek the avant-garde,” Regan says, “but now, people want predictability."

Regan also created digital works for Vermont News Guide that pay homage to another warmly familiar American artist, Norman Rockwell. Regan nodded to Rockwell’s 1943 Saturday Evening Post cover depiction of Rosie the Riveter, only the modern Rosie is making face masks. Regan also created a take on Rockwell’s “Freedom From Fear,” as quarantining parents care for a small child.

Steve Melcher, creator of an ongoing series of art spoofs he has titled “That Is Priceless,” says that events depicted in fine art provide a helpful historical perspective.

“When we look at art, we see that humanity has been going on a long time — and crazy stuff has been happening for millennia — and you think: ‘Okay, maybe I’m trapped in the house with my family in the middle of a global pandemic, but it could be worse,” says Melcher, a comedy writer and producer who has worked for David Letterman and Martin Short, among others. “We could be in the middle of a 40-day worldwide flood, or turned into pillars of salt, or beheaded by Henry VIII, or burning in hellfire, or any number of nasty things you run into browsing the Louvre’s website.”

Sanjit Sethi, the president of the Minneapolis College of Art and Design, says these images reminded him of the words of the poet Rumi: “New organs of perception come into being as a result of necessity. Therefore, O man, increase your necessity, so that you may increase your perception.”

The pandemic has focused us on necessity, he points out, so we perceive the world anew — and have a desire to express what we’re noticing.

“It is a desire not merely for a greater degree of connectivity, but I think a greater degree of understanding. Not merely to witness, but to participate,” he notes. “Not solely to drive by, but to immerse ourselves.”

No comments:

Post a Comment