Our Favorite Lit Hub Stories From 2020

December 23, 2020From essays to interviews, excerpts and reading lists, we publish around 300 features a month. And while we are proud of all the 3,000+ pieces we’ve shared in 2020, we do have our personal favorites. Below are some of the pieces we loved best on Lit Hub from this very long year.

“On the Language of Nonviolence and the US Criminal Justice System” by Michael Fischer

Michael Fischer’s brilliant consideration of the term “nonviolent”—how it cleaves society into the redeemable and the irredeemable, and in the process allows the invisible violences of American institutions to continue—stayed with me long after I first read it. Fischer himself served a state prison sentence for a nonviolent offense and describes how his re-entry, and the continuation of his writing career, was affected and aided by his state-assigned label. In condemning the system that would punish individual-level violence while failing to address institutional violence, Fischer lets no one off the hook: After his release, he writes, “I reproduced the same cowardly, unexamined logic that many of us use to claim superiority over others.” Unlearning how to do that, and opening oneself to the awareness of another perspective, is a humbling, challenging process. –Corinne Segal, Senior Editor

VIDEO FROM LIT HUB:

Lee Child talks to Heather Martin at the Hay Festival Winter WeekendAd ends in 27s

“Editing Larry Kramer, a Man Larger than Life” by Helen Eisenbach

After Larry Kramer died this past spring, a number of tributes and not-quite-tributes reckoned with the complicated legacy of a man who, through sheer force of will and personality, achieved the near-impossible by bringing national attention to AIDS while driving many of his closest allies completely insane. This one was my favorite. Helen Eisenbach was a young editor who spotted the excellence of The Normal Heart at an early production and, in short order, bought it for her publisher, NAL/Dutton. Kramer is remembered here in all his impassioned fury: his endless calls to Eisenbach, his demand that the publisher lower the price of the book for the sake of accessibility to the community, his insistence that those who disagreed with him were murderers. Still, she writes—and her full essay shows—he was “a man ahead of his time.” –CS

“How I Hustled Hundreds of Dollars of Free Tacos for the Literary World” by MM Carrigan

“The Taco Bell Literature Movement is upon us,” MM Carrigan declares in this essay-slash-manifesto, speaking directly to anyone who’s ever felt cast out, misunderstood, or let down by the publishing world. The story of how Carrigan came to create Taco Bell Quarterly, a Taco Bell-themed literary magazine (really), begins with rejection, ends with the existence of a publication that has drawn national press, and features some straight talk and free tacos along the way. Read it and “dream más.” –CS

*

I am going to cheat here and choose more stories than I was told I could. Honestly, that the following writers were able to do what they did during this darkest of years elevates these essays a notch higher. –Jonny Diamond, Editor in Chief

“The Wolves of Stanislav: An Improbably True Parable for the Pandemic Age” by Paul Auster

Somehow Paul Auster wrote an entirely true parable-within-a-parable about the old bloodlands of Europe and the improbably large wolf packs that once roamed the outskirts of Stanislav… that was in fact about the slow creeping horror of a growing American pandemic. –JD

“On Not Meeting Nazis Halfway” by Rebecca Solnit

Not too long into the first year of the Trump administration Rebecca Solnit wrote what will stand as the most important diagnosis of a pathological presidency; two weeks after the end of that presidency she articulated what millions of us were feeling with a clarity we hadn’t quite achieved on our own. And I quote: “Who the hell wants unity with Nazis until and unless they stop being Nazis?” –JD

“Is There a Better Way for the Left to Talk About American Christianity?” by Marie Mutsuki Mockett

It was a hard year for nuance (it’s been a hard decade for nuance). So I loved Marie Mutsuki Mockett’s unexpected and honest account of the time she spent with a harvesting crew near Oklahoma City, finding complexity and value in a deeply American kind of faith that is too often dismissed as a byproduct of toxic politics. –JD

“Going Quiet as the World Goes Loud: On Private Anxiety in a Very Public Pandemic” by Brandon Taylor

“In the back of the ambulance, I thought about dying. I thought about the people who go in and don’t come out.” Brandon Taylor has always been a revelation to me as a writer and this essay, which gets deeper into the experience of life in the pandemic summer of 2020 than almost any I have read, is one more example of why his writing will endure. –JD

“The Incoherence of Hate: Reading The Protocols of the Elders of Zion” by Daniel Torday

It is one thing to retweet a gif of a Nazi getting punched (which, yes, please continue punching Nazis) but it is entirely another to wade into the origins of 20th-century antisemitism and make the ugly connections to the toxic idiocy of 21st-century conspiracy theorists. So we should all be grateful to Daniel Torday for actually reading The Protocols of the Elders of Zion and for unpacking an unhinged syntax of bigotry that has found new life in the mad eructations of QAnon. –JD

“On the Solstice: Deep Winter Dreams of the Spring to Come” by Rick Bass

This was the piece we needed on the darkest day of the darkest winter in many generations of American life. There isn’t much sense in trying to summarize this Rick Bass essay, so I’ll just quote from it at length:

Even the great bears themselves, sleeping like astronauts beneath us in winter, slow their heartbeats at the solstice to almost zero: only a very few beats per minute. But in that rarity, power, waiting, power, building.

I believe they dream of beauty: of the yellow lilies of Easter, and the wild violets and rank mushrooms and pink flesh of trout; of berries, of stones, of antlers, feathers, moss, fire. And fire’s warmth.

These are the dreams we all need right now. –JD

“A Toy, a Tool, a Piece of Art: Sarah Haas on What a Book Can Be” by Sarah Haas

Damn. I was floored by this investigation of the value of the book as object, and of the value of our obsession with the Book as Object, which ranges from William Tyndale to the Nazis to Marie Kondo, and how it is complicated by the constant loom of the internet, not to mention those who seem to imagine that just having books makes them better humans. “Desperately, I want to believe that a book can help one person understand another, that there might be a way to solve the problem of what to do with another’s pain, but I don’t think empathy is logically possible nor morally admirable,” Haas writes. Instead, ultimately, she lands on an idea of books not as ways to understand our friends, but as friendships themselves. If that sounds far out, well, go read the essay and then get back to me. –Emily Temple, Managing Editor

“A Secret Literary Love Hidden in the Margins of The Price of Salt” by Antonia Angress

In this essay, Angress writes about buying a used copy of Patricia Highsmith’s classic soon after realizing her own bisexuality—and finding it covered in marginalia, an elaborate, fractured love letter from one woman to another, transcribed into the margins of one of the best novels about two women in love. This is, obviously, the dream: one of the many reasons I love reading old books is that they often give you a sense of their previous lives, or at least the possibility thereof, though not usually as clearly as this. But Angress also gets at one of the most intense pleasures of reading, one I rarely see articulated: “Sometimes I say that I like to read novels for the most selfish of reasons: to entertain myself,” she writes. “But that’s not the whole truth. I read fiction because it’s a way of rewriting myself. . . . And I worry, sometimes, that I’ve rewritten myself too many times.” Read if you too want a moving personal essay, a work of smart criticism, and a story about finding a mysterious treasure all in one. –ET

“The 89 Best Book Covers of 2020” by Emily Temple

Look, I’m sorry, I realize this piece is technically by me, but all I did was send the emails and write the intro, so I don’t feel bad about admitting that this is always one of my favorite roundups (this is the fifth year we’ve done it!). The credit really goes to all of the professional book cover designers who took the time to send me their lists of their favorite covers of the year (not to mention the designers who made all the covers in question). Every year, I love to see their choices and hear why they admire them—and while I love to see which covers rack up the accolades, it’s even better to be surprised by the lesser-known covers I had never seen before. Plus, it winds up being just a treasure trove of beautiful things, which honestly, after the year we’ve all had, is nothing to kick out of bed. –ET

“Wicked Wouldn’t Have Been What It Is If I Hadn’t Written the Novel by Hand” by Gregory Maguire

If you, like me, are a dork who compulsively fills her home with new blank notebooks and carries one around with her always, you will be delighted by Gregory Maguire’s ode to the act of writing in longhand. (If you’re a theatre dork, you should also check it out, because this is tried and true advice from the man who penned Wicked. Bonus: it includes a scan of his initial idea page which contains the sentences: “Glinda was a media star, shallow and self-serving. The monkeys her only true love.”) In this piece, Maguire questions what we’ve lost when we gained the ease of the typed word. He praises the slow and cramped fingers, the discomfort of the wrist, as chances to seriously consider your next word. He likens writing by hand to the imaginative creation of a child, and he encourages you to free yourself of the shackles of language in order to write: “Drawing is at the core of language, no less so than breathing is at the core of singing. To write a beautiful and captivating word—let’s say, oh, why not, ‘Oz’—is first to master the art of drawing a circle.” –>Katie Yee, Book Marks Associate editor

“About That Wave of Anti-Racist Bestsellers Over the Summer…” by Katherine Morgan

For the past few months, all of #bookstagram has been flooded with VSCO-filtered photos of Ibram X. Kendi’s How to Be an Antiracist, Robin DiAngelo’s White Fragility, Ijeoma Oluo’s So You Want to Talk About Race—you get the idea. Books that had been out for a while were finally getting the attention they deserved. Good. But how genuine is all this, really? Only a few weeks after George Floyd’s murder, and there were fewer people saying his name. A few microaggressions later, and you might be quite convinced that no one is actually reading any of these books at all. Katherine Morgan (a former bookseller at Powell’s) begins her piece: “During the summer of 2020, I spent countless hours helping irate customers cancel their orders of popular anti-racism books.” Yikes! In this honest and incisive essay, Morgan details the painful irony of the racist encounters she endured as a bookseller at the height of #BLM and #BlackWritersMatter. (Katherine Morgan, if you are reading this: I am sorry. People suck.) Everyone, please check your privilege and your performative allyship at the door and read her essay at once. –KY

“Baba Yaga Will Answer Your Questions About Life, Love, and Belonging” by Taisia Kitaiskaia

This is a fun one! For the fairytale lover: Lit Hub gives you Taisia Kitaiskaia’s advice column, featuring the ventriloquistic powers of the Baba Yaga, an unpredictable Slavic witch that’s rumored to live in the forest and offer sage advice to those who seek it (or, you know, she might eat you as a snack; it’s pretty much 50/50). Responding to real questions that readers have sent in, Kitaiskaia channels the wise, old crone in what can only be described as a charming piece, full of strange turns of phrase and funny quips. How can you tell which type of witch you are? “Cows speak when you are alone. Eating porridge morningly, you crave to make a thing with sucking roots.” How can you find your role in the revolution? “Pull yr Intellect from yr body like the spine from a fish.” Your plants are dying? “Listen close, may-be they do not wish to live in yr house at all.” Take note, @ everyone who thinks they are a plant lady in quarantine. –KY

“Why Are We Fascinated by Strange Faces?” by Namwali Serpell

This is the kind of essay that you have to buckle in for because its argument is so smart, so capacious, and so bold. In this piece, Namwail Serpell suggests that the general fascination with strange faces is not simply a fetish for the grotesque but a kind of aesthetic impulse that cannot be totally disentangled with the “pleasures of monstrosity.” She begins with her encounter of the “Smiling Disease” exhibit at the Venice Biennale, which launches her consideration of iconic historical figures like The Elephant Man, Cleopatra, and Michael Jackson. “What can’t be denied,” Serpell says. “Is that Michael Jackson, Joseph Merrick, and Cleopatra each made their strange faces a shameless spectacle.” I loved this essay because it offers us some space to think about beauty, desirability, and art with a different orientation, one that sits with other, more unruly attachments and affects. –Rasheeda Saka, Editorial Fellow

“Who Gets to Be a Sympathetic Character in The Undoing?” by Olivia Rutigliano

There was such an uproar following the season finale of HBO’s hit-show The Undoing that I succumbed to the hype and watched the entire series over the course of three days. What I thought would be amazing (because the uproar seemed to be quite positive) turned out to be utterly dissatisfying. And a day later, I found that our very own Olivia Rutigliano articulated why The Undoing missed the mark; and she did so with such clarity and care that I texted my friend the piece, saying “I’m crying, this is it.” In the essay, Rutigliano argues that the show’s “simplistic methodology,” which mobilizes racist tropes, fails to position the very woman (Elena) who was murdered by a sociopathic man (and cheating husband) as worthy of sympathy, in favor for a rich white woman (the man’s wife). “Inadvertently, through this all,” says Rutigliano. “The Undoing represents sympathetic victimhood as a privilege, itself—and a privilege given to white women rather than Women of Color.” Even more, Rutigliano locates this argument within the state of current politics, showcasing the magnitude of the show’s implications on our public consciousness. The essay is a beautiful read and I was happy to find words that could explain why and how a show could leave such a bitter aftertaste in my mouth. –RS

“Love in a Time of Terror,” by Barry Lopez and “Salutations In Search of,” by Patricia Smith

Love and mourning—2020 felt satanically designed to make it impossible to do either. All when we needed both more than ever. How to climb out of this soul-sick time without love? How to appreciate what we’ve lost without mourning? The challenge of these questions was met over again this year by writers across the globe. I was so grateful for essays this year by Masha Gessen, Zadie Smith, Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor, Paul Hendrickson, Semezdin Mehmedinovic, Valzynha Mort. Poems by Tracy K Smith, Lawrence Joseph, and Terrance Hayes. I could name a hundred pieces from this site, let alone fellow magazines and newspapers—we’re all in this together, all of us want a better world—but two changed my heart fundamentally. In “Love in a Time of Terror,” Barry Lopez argues that love could be the most powerful force in guiding our interactions on this planet—in encounters, across landscapes not our own. In a time when so many types of encounters have begun to feel doomed, Lopez manages to redefine curiosity away from exploitation, and toward respect and love. This is an astonishing essay about environmentalism, ethics and the heart. Simultaneously, Patricia Smith’s poem from earlier this summer seeks a way to address the many who have died, who have been murdered, who have been taken in the centuries of American violence against people of color. In lines syncopated by rage and grief, she forms a psalm of mourning. It reminds you how all writing began with song. ”Dear wild tumultuous, your mouth,” she writes. “Dear God/Your mouth, in fevered skirmish with the tongue,/ denying sound for rope or goldenrod./ Dear mouth, still bulging with Atlantic, wrung/into its new.” I am in awe at writing which can take us back to our fundamental beginnings in this way. –John Freeman, Executive Editor

The Black Dahlia: The Long, Strange History of Los Angeles’ Coldest Cold Case by Miles Corwin

In this long essay, Miles Corwin chronicles the meticulous research of Larry Harnisch, a fact-checker who has spent twenty-four years searching for the murderer of Elizabeth Smart, known as “The Black Dahlia,” who was gruesomely murdered in 1947. Though the case is one of the most famous unsolved murders in history, and most of its secrets are now lost to time, Harnisch actually probably manages to uncover the killer. The documentary filmmaker Errol Morris recently lamented on Twitter that great journalism has become confused with ‘literally solving murders,’ reminding folks that it is vastly possible to do sensational work if you don’t happen to solve an unsolvable crime. That being said, I do want to note the extraordinary and painstaking work that Harnish has accomplished in (probably) solving this crime. –Olivia Rutigliano, CrimeReads Assistant Editor

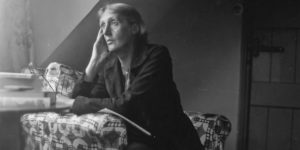

Interpreter of Maladies: On Virginia Woolf’s Writings About Illness and Disability by Gabrielle Bellot

>Every piece that Gabrielle Bellot writes is beautiful, but I was so moved by this extremely recent piece of hers, about Virginia Woof’s reflections on illness and trauma (in light of her many bouts of influenza). Gabby gently lays her own experiences with anxiety and COVID-19 alongside her analyses of Woolf’s writings. The richness, the depth of the rumination completed by both these two incredible women, these two exquisite writers, made this piece feel so incredibly soothing. Woolf, Bellot notes, grew to notice that illness was not a site of exploration for most writers, and turned her earlier denials of the seriousness of illness into a place to reflect on the body. And Bellot does the same, to incredibly moving ends. –OR

“Do All Pugs Go To Heaven?” by Scott Cheshire and “Why We Can’t Stop Loving the Most Troublesome Pets” by Matt Sumell

Two very different but equally wonderful, and quietly devastating, pieces about the joys and agonies of loving dogs, even when age and ailments have made instances of the latter all-too frequent. For Sumell, that dog is Seymour—a malady-plagued rescue mutt, the latest in a line of “hard-luck cases I’ve lost over the last few years, each of them sweet and doomed, each of them dealt terrible and unfair hands by whichever lazy, fat-fingered amateur you choose to believe in.” For Cheshire, that dog is Olive—a fawn-colored, Real Housewives-loving, fourteen-year-old pug who passed away earlier this year. Having become a dog parent myself for the very first time earlier this year (to a springer spaniel puppy who will continue to avoid traffic and blue-green algae and who is going to live forever, ok?), both pieces broke me a little bit. –Dan Sheehan, Book Marks Editor

“The Philosopher and the Detectives: Ludwig Wittgenstein’s Enduring Passion for Hardboiled Fiction,” by Philip K. Zimmerman

“The scene is London; the year, 1941. Ludwig Wittgenstein, likely the greatest philosopher of the twentieth century, has taken a hiatus from his Cambridge professorship to do ‘war work’ in a menial position at Guy’s Hospital.” That’s how my favorite story of the year began, in good noir fashion, bordering on the gothic, and soon enough we’re launched into the desperate, heady days of wartime and postwar England and its dowdy academic life being quietly subverted by a brilliant, revolutionary mind hellbent on getting to the root, the very essence of language itself. And the mind belongs to Wittgenstein. And when he’s not thinking about philosophy he’s devouring American detective magazines, which he receives from friends and colleagues by the binful. He complains about wartime rations on paper cutting his supply of mystery short. His ideas, crackling and opaque, somehow connect to what he’s reading in those same magazines, stories about hardboiled detectives working seedy cases on the streets of American cities the philosopher will never know. Philip Zimmerman weaves together all these disparate pieces into an illuminating and moving narrative of a mind in the throes of passion and invention, and somehow it keeps coming back to those detective magazines. This is a beautiful portrait in noir. –Dwyer Murphy, CrimeReads editor in chief

“Ten Writers Reflect on Their First Big YES” by Benjamin Schaefer

After a year of feeling completely incapable of writing (see Irina Dumitrescu’s “Something Is Wrong on the Internet: A Study in Pandemic Distraction” for a too-real rendering of my state of mind), I bring to you, from the annals of January, a feel-good collection of anecdotes about the moments when ten writers went from what-am-I-even-doing-here vibes to “Oh, it’s almost like I’m a real writer now” (Rowan Hisayo Buchanan). I loved to read how each interpreted Benjamin Schaefer’s question of their first big yes, be it a begrudging magazine assignment (Eva Hagberg), the first piece of fan mail (De’Shawn Charles Winslow), a yes to oneself (Francisco Cantú), or even a no (C Pam Zhang). It was a delight to reread eleven months later, and the sort of reflective and sappy question I’ll be foisting upon my unsuspecting writer friends as we close out the year. –Eliza Smith, contributing editor

“Justice for the Invisibles, by the Invisibles: a Brief History of Nontraditional Voices in Crime Fiction” by Christopher Chambers

There’s a wonderful thing happening in crime fiction these days, and one that we’ve been waiting for for some time: the sidekicks, the best friends, and the marginalized are no longer relegated to the interpretation of a white male narrator, but finally telling their own stories. In this brilliant and engaging essay, Christopher Chambers interviews several crime writers to capture the present moment of transition. Chambers’ quote from S.A. Cosby puts it best: “The sidekicks and set dressing are now the protagonists because the people often most misrepresented in the genre are now writing their own stories…we are experiencing an inflection point.” –Molly Odintz, CrimeReads Senior Editor

“Linda, Interrupted” by Sarah Weinman

While Margaret Millar and Ross Macdonald were indisputable masters of mid-century crime fiction, their legacy as parents is a bit more mixed. After you read this essay from Sarah Weinman about the Millars’ daughter Linda, you might even find their nurturing skills to be downright abominable. In this long-form essay, Weinman lays out the harsh details of a short and tragic life, of a young woman in pain, and of a narcissistic and neglectful couple who drove their own child to an early grave. –MO

“How Does Garth Greenwell Make Such Wonderful Sentences?” by Christian Kiefer

Garth Greenwell’s prose has been lauded for accurately capturing the irrational dream logic of desire, but it turns out his sentences are anything but mystical. (And that’s a good thing!) In this essay, Christian Kiefer zooms in and shows us how Greenwell bends traditional grammar rules to create internal logic in his sentences. The piece’s attention to detail recalls Gary Lutz’s lecture “The Sentence is a Lonely Place,” and feels like a little masterclass. –Walker Caplan, staff writer

“A Feminist Critique of Murakami Novels, with Murakami Himself” by Mieko Kawakami and Haruki Murakami

The tropes of Haruki Murakami novels are well-worn at this point: cats; jazz records; urban malaise; and, most concerningly for some, women that function as gateways for a male protagonist’s transformation. In this transcribed interview, Breasts and Eggs author Mieko Kawakami, one of Murakami’s favorite working novelists and a Murakami admirer herself, questions Murakami about the roles female characters play in his work. Murakami’s answers are unguarded, and the authors’ mutual enjoyment is palpable. –WC

“In Praise of Weird Literary Couples” by Amy Bonnaffons

Thinking back to February of this year when we had the luxury of dismissing Valentine’s Day plans, Amy Bonnaffons’ list of weird literary couples was a fun, quirky list of books that could supplement an awkward date night. But now, deep in Zoom happy hours and the darkest nights of winter, I’ve found her list that couples monsters and housewives, women and merman does more than “remind us of love’s inherent strangeness.” Now we are reminded of its necessity. Here, Bonnaffons has collected eight excellent books of strange couplings, plus she’s also written the best description of love I’ve ever read:

Love is hairy, absurd, and dangerous. Of course it’s sometimes mundane and boring too, but only in the way that if you had a pet python named Carl you’d probably get used to him after a while, fail to even notice him sometimes, think of him mostly as an obligation—shoot, who will feed Carl when I go to that conference in Tampa?—and then once in a while you’d catch a glimpse of the terrarium in the corner and think holy shit I live with this thing that could kill me, Carl could totally kill me, and then you’d walk over and lift Carl out of his terrarium and marvel not only that Carl chooses every day not to kill you but that he exists in this world at all: millions of years of evolution culminating in the sleek muscled cable of his body, the dizzying beauty of his scales, the deep black knowing in his tiny beadlike eyes.

–Emily Firetog, deputy editor

No comments:

Post a Comment