Biden to the Rescue?

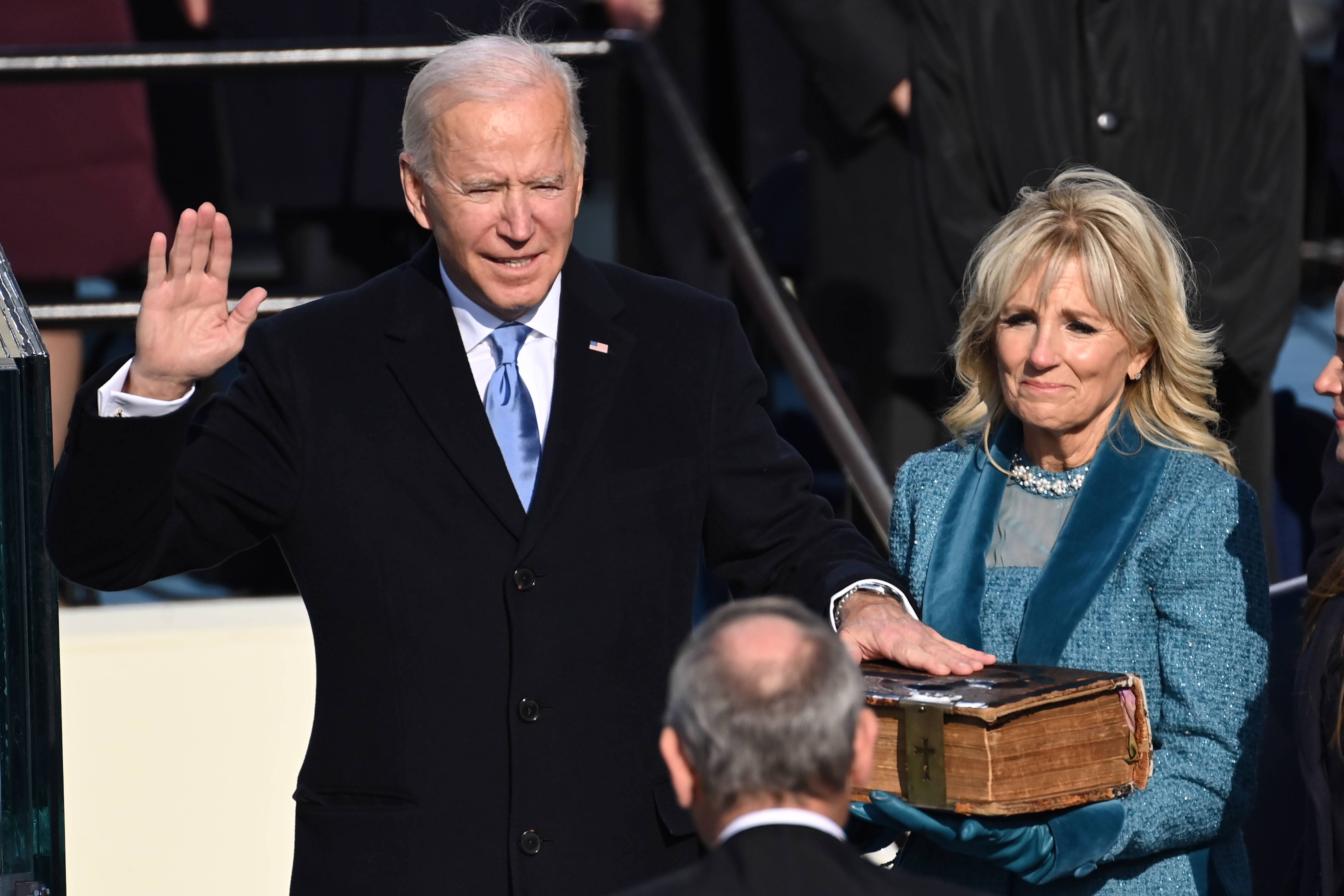

In his January 20 inaugural address, US President Joe Biden called for unity following America’s turbulent and occasionally violent transition, acknowledging the country has “much to repair, much to restore, much to heal.” But how can Biden prevent a revival of Trumpism at home and restore the United States’ standing with its partners and allies?

In this Big Picture, Nobel laureate economist Joseph E. Stiglitz cautions that overcoming the longstanding problems that gave rise to Donald Trump’s toxic presidency – not least rampant inequality – will require more than what one president can accomplish in a single presidential term. But among the most urgent priorities, argues MIT’s Daron Acemoglu, is to acknowledge the weaknesses of America’s democratic institutions, most of which have been failing and are in desperate need of repair and reform.

But America’s economic institutions also are failing, and Laura Tyson, a former chair of President Bill Clinton’s Council of Economic Advisers, and McKinsey & Company’s Lenny Mendonca urge the Biden administration to draw inspiration from European and – especially – Californian market capitalism in order to “build back better” after the pandemic. And Jayati Ghosh of International Development Economics Associates highlights four immediate steps Biden can take to boost the global economy.

On the diplomatic front, Kemal Derviş of the Brookings Institution calls on Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris to champion liberal democracy far more consistently at home and abroad than the US has done in the past. To that end, Harvard University’s Joseph S. Nye, Jr. considers which actions – ranging from broadcasts and economic aid to military invasions – Biden might favor in trying to influence the domestic affairs of other sovereign states.

Whither America?

Fortunately, Joe Biden will assume the US presidency on January 20. But, as the shocking events of January 6 showed, it will take more than one person – and more than one presidential term – to overcome America’s longstanding challenges.

NEW YORK – The assault on the US Capitol by President Donald Trump’s supporters, incited by Trump himself, was the predictable outcome of his four-year-long assault on democratic institutions, aided and abetted by so many in the Republican Party. And no one can say that Trump had not warned us: he was not committed to a peaceful transition of power. Many who benefited as he slashed taxes for corporations and the rich, rolled back environmental regulations, and appointed business-friendly judges knew they were making a pact with the devil. Either they believed they could control the extremist forces he unleashed, or they didn’t care.

Where does America go from here? Is Trump an aberration, or a symptom of a deeper national malady? Can the United States be trusted? In four years, will the forces that gave rise to Trump, and the party that overwhelmingly supported him, triumph again? What can be done to prevent that outcome?

Trump is the product of multiple forces. For at least a quarter-century, the Republican Party has understood that it could represent the interests of business elites only by embracing anti-democratic measures (including voter suppression and gerrymandering) and allies, including the religious fundamentalists, white supremacists, and nationalist populists.

Of course, populism implied policies that were antithetical to business elites. But many business leaders spent decades mastering the ability to deceive the public. Big Tobacco spent lavishly on lawyers and bogus science to deny their products’ adverse health effects. Big Oil did likewise to deny fossil fuels’ contribution to climate change. They recognized that Trump was one of their own.

Then, advances in technology provided a tool for rapid dissemination of dis/misinformation, and America’s political system, where money reigns supreme, allowed the emerging tech giants freedom from accountability. This political system did one other thing: it generated a set of policies (sometimes referred to as neoliberalism) that delivered massive income and wealth gains to those at the top, but near-stagnation everywhere elsewhere. Soon, a country on the cutting edge of scientific progress was marked by declining life expectancy and increasing health disparities.

The neoliberal promise that wealth and income gains would trickle down to those at the bottom was fundamentally spurious. As massive structural changes deindustrialized large parts of the country, those left behind were left to fend largely for themselves. As I warned in my books The Price of Inequality and People, Power, and Profits, this toxic mix provided an inviting opportunity for a would-be demagogue.

As we have repeatedly seen, Americans’ entrepreneurial spirit, combined with an absence of moral constraints, provides an ample supply of charlatans, exploiters, and would-be demagogues. Trump, a mendacious, narcissistic sociopath, with no understanding of economics or appreciation of democracy, was the man of the moment.

The immediate task is to remove the threat Trump still poses. The House of Representatives should impeach him now, and the Senate should try him some time later, to bar him from holding federal office again. It should be in the interest of the Republicans, no less than the Democrats, to show that no one, not even the president, is above the law. Everyone must understand the imperative of honoring elections and ensuring the peaceful transition of power.

But we should not sleep comfortably until the underlying problems are addressed. Many involve great challenges. We must reconcile freedom of expression with accountability for the enormous harm that social media can and has caused, from inciting violence and promoting racial and religious hatred to political manipulation.

The US and other countries have long imposed restrictions on other forms of expression to reflect broader societal concerns: one may not shout fire in a crowded theater, engage in child pornography, or commit slander and libel. True, some authoritarian regimes abuse these constraints and compromise basic freedoms, but authoritarian regimes will always find justifications for doing what they will, regardless of what democratic governments do.

We Americans must reform our political system, both to ensure the basic right to vote and democratic representation. We need a new voting rights act. The old one, adopted in 1965, was aimed at the South, where disenfranchisement of African-Americans had enabled white elites to remain in power since the end of Reconstruction following the Civil War. But now anti-democratic practices are found throughout the country.

We also need to decrease the influence of money in our politics: no system of checks and balances can be effective in a society with as much inequality as the US. And any system based on “one dollar, one vote” rather than “one person, one vote” will be vulnerable to populist demagogy. After all, how can such a system serve the interests of the country as a whole?

Finally, we must address the multiple dimensions of inequality. The striking difference between the treatment of the white insurrectionists who invaded the Capitol, and the peaceful Black Lives Matter protesters this summer once again showed to those around the world the magnitude of America’s racial injustice.

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has underscored the magnitude of the country’s economic and health disparities. As I have repeatedly argued, small tweaks to the system won’t be enough to make large inroads in the country’s ingrained inequalities.

How America responds to the attack on the Capitol will say a lot about where the country is headed. If we not only hold Trump accountable, but also embark on the hard road of economic and political reform to address the underlying problems that gave rise to his toxic presidency, then there is hope of a brighter day. Fortunately, Joe Biden will assume the presidency on January 20. But it will take more than one person – and more than one presidential term – to overcome America’s longstanding challenges.

US Institutions After Trump

It would be a mistake for Americans to take comfort in the fact that their democratic institutions survived four years of attacks by Donald Trump, culminating in the January 6 insurrection at the US Capitol. In fact, most of these institutions have been failing and are in desperate need of repair and reform.

BOSTON – The storming of the US Capitol by Donald Trump’s supporters on January 6 may be remembered as a turning point in American history. The insurrection, incited by the president himself, has raised profound questions about the kind of political institutions future generations will inherit.

Two narratives have come to describe this nadir of an already-tumultuous presidential transition in the United States. The first frames the Capitol insurrection as a singular failure of US institutions, which implies that the solution is to clamp down on right-wing extremists, social-media echo chambers, and their mainstream enablers.

But while such measures are long overdue, this narrative fails to capture the extent to which the Capitol attack was a direct result of Trump’s presidency, or the economic hardship and social grievances that led to Trump’s rise. In addition to leaving the country alarmingly polarized, Trump’s single term also fundamentally damaged US institutions, and decimated political norms that a well-functioning democracy needs.

The second prevailing narrative is even wider of the mark. It celebrates those Republicans – like Georgia’s Voting Systems Implementation Manager, Gabriel Sterling – who stood up against Trump’s falsehoods and attempts to overturn the election. This narrative frames the failure of the MAGA coup as inevitable, owing to the fundamental strength of US institutions. And yet, this mythical institutional resilience has been notably absent for most of the past four years. Even after they themselves were attacked, a majority of congressional Republicans were happy – or at least willing – to go along with a presidential agenda that threatened the future of the Republic.

Likewise, while many have praised the judiciary for maintaining its independence, the courts were only partly effective in stopping Trump’s unlawful decrees. The sheer scale of cronyism and corruption – with the Trump family routinely mixing government and private business – has yet to be fully investigated or appreciated. The Republican Party brushed off Trump’s attempt to withhold $400 million in military aid unless Ukraine launched an investigation into Joe Biden and his son.

Republicans were also silent when Trump fired Gordon D. Sondland, his ambassador to the European Union, and Lt. Col. Alexander S. Vindman, following their testimony in the impeachment proceedings. Nor did they speak out against the dismissal of the intelligence community’s inspector-general, Michael K. Atkinson. Far from preventing the firing of inspectors-general for doing their jobs, US institutions were approaching a breaking point by the end of Trump’s term.

It is unlikely that many US institutions would have survived another four years of Trump, considering that they were not particularly strong to begin with. Before Trump, polarization in Congress had already taken a toll on political effectiveness, and the executive branch had gradually been strengthened vis-à-vis the legislative and judicial branches of government.

To be sure, the framers of the US Constitution wanted a strong federal government. Because they did not fully trust the judgment of their fellow citizens, they institutionalized several non-democratic elements, not least a highly malapportioned voting system (especially for the Senate) and the Electoral College. But these features have become particularly problematic for the current age, because civil society and the ballot box were always going to be the only real defense against a politician like Trump.

It would thus be a colossal mistake to take comfort in US institutions’ survival of what Trump wrought on January 6. To leave better institutions to future generations, we must acknowledge their weaknesses and start rebuilding them. This will not be easy. No society has ever devised a foolproof way to overcome deepening political polarization. How does one convince tens of millions of Trump supporters that they have been manipulated and fed lies for years?

One starting point is to address the economic hardships that many (though certainly not all) Trump supporters have experienced. Much more can be done to increase the incomes of workers who do not have a college degree. In addition to higher minimum wages, the US needs a new growth strategy to increase the supply of good jobs for workers at all skill levels. Of course, even with this, concerns within many communities about changing social and cultural dynamics would remain.

Beyond individual policy measures, we need to re-evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of institutions. Some institutions would be difficult to reform even if there were broad agreement on what should be done. Others are easier to fix. Most important, we need better independent monitoring mechanisms. The next Trump-like figure should not be able to fire inspectors-general for doing their jobs, nor should a president’s family be able to profit from his or her office.

A greater degree of professionalism in the civil service is also important, and can be achieved in part by limiting the scope of political appointments and dismissals. In the case of expertise-based organizations with a clear mandate (such as the Environmental Protection Agency or NASA), it does not make sense for each new administration to install a contingent of cronies at every level of the hierarchy.

More fundamentally, US federal institutions have a public-trust problem that will need to be addressed through greater transparency. Yes, too much transparency in government deliberations and decision-making can lead politicians and civil servants to pander to voters. Yet the first priority for the federal government today must be to rebuild public trust after decades of growing estrangement. Shedding more light on relationships between corporate lobbies and politicians would be a good place to start.

Last but certainly not least, Electoral College reform must be on the agenda. Although a constitutional amendment seems unlikely in the current political environment, proposals such as the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact could open a path to bipartisan reform, making it harder for the next American populist to ride to power on the support of a disaffected minority of the electorate.

Capitalism We Can Believe In

President-elect Joe Biden’s call to “build back better” after the pandemic is an invitation to renovate America’s outdated neoliberal version of capitalism. The more successful variants of market capitalism found in Europe or, better, in California, point the way forward.

BERKELEY – Even before the COVID-19 pandemic ravaged the United States and other developed economies, trust in capitalism had eroded around the world, particularly among young people. In 2019, when unemployment was low and wages were rising, 56% of respondents to a global survey by the Edelman Trust Barometer nonetheless believed that “capitalism as it exists today does more harm than good.” In the US, specifically, only 51% of young adults in a Gallup poll that year gave capitalism a “positive” rating, while 49% approved of socialism.

Growing distrust of capitalism follows from its failure to address major socioeconomic challenges, not least climate change and inequalities in opportunity, income, and wealth. While private incentives under capitalism are good at stimulating efficiency, growth, and innovation, they also generate unequal income and wealth distributions (even in a context of intense competition), often at odds with social norms of fairness. Moreover, capitalist systems tend to underinvest in public goods like education, health care, and social insurance – all critical factors in the pandemic response – while also discounting negative externalities such as greenhouse-gas emissions.

These shortcomings of capitalism are predictable, but they are remediable through public policies and institutions. Tax and transfer policies and minimum wages can reduce income and wealth disparities, just as public investment in education, training, and health care can enhance opportunity by providing access to good jobs and fostering the creation of new enterprises. Likewise, a price on carbon dioxide and regulations limiting or banning carbon emissions can help the world avert the existential threat of climate change.

Critics of capitalism often miss (or choose to ignore) that there is no single canonical model. Europe’s various “social market” models differ significantly from the neoliberal variant in the US. And even within the US, there are important differences between states and localities.

Some of these distinctions have been highlighted in the responses to the COVID-19 pandemic and recession. All advanced economies have deployed unprecedented levels of fiscal and monetary stimulus in the face of “K-shaped” or “dual” recessions in which lower-wage workers have suffered disproportionately more than other cohorts. Unlike the US, Germany and several other European countries have deployed measures specifically designed to keep as many workers as possible in their jobs. Because these countries have generous social insurance and benefits, including sick leave and family leave, workers and their families have been able to cope with both COVID-19 and sudden drops in their incomes.

Differences in national health-care models have also become more apparent. Unlike European capitalist systems that provide universal coverage, 14.5% of America’s non-elderly population (ages 18-64) remains uninsured. Moreover, owing to America’s heavy reliance on employer-based insurance, the pandemic has pushed at least 15 million more workers at least temporarily into the uninsured pool.

With their strong public-health systems, many European countries were also better equipped to carry out widespread testing and vaccine distribution. The US, meanwhile, has utterly failed to contain the virus, and is now delegating the vaccination campaign to under-resourced state and local authorities.

In another contrast with the US, Europe has dedicated about one-third of its massive stimulus program to investments aligned with its commitment to achieve carbon neutrality by mid-century. America’s federal stimulus measures have been silent on climate with few conditions of any kind.

Within the US, individual states’ responses to the COVID-19 crisis reflect different variants of capitalism. In California, Governor Gavin Newsom’s recent 2021-22 budget proposal reveals some distinctive features. In terms of health-care coverage, California remains a national leader with a Medicaid program covering more than 13 million people. Despite the pandemic-induced recession, the state is increasing its minimum wage to $14 per hour in 2021, on track to realize the target of $15 per hour in 2022 for all businesses employing 26 or more workers; many municipalities, including Los Angeles and San Francisco, have already achieved or exceeded the $15 target. (On January 1, 2021, 20 other states also raised their minimum wages, whereas the US federal minimum wage has remained unchanged at $7.25 per hour since 2009.)

California has also expanded coverage of its Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and Young Child Tax Credit to include undocumented workers who are otherwise denied the benefits of federal stimulus packages. Together, these tax credits applied to 3.6 million California households in 2020, adding $1 billion in total income. The state also passed new legislation significantly expanding unpaid family-leave rights. Employers with as few as five employees now must provide this option as well as more time for paid sick leave for workers forced to self-isolate or quarantine as a result of COVID-19 exposure or diagnosis.

Looking ahead, Newsom has proposed an additional $600 one-time cash payment to all taxpayers who are eligible for the state’s EITC in 2021. His proposed 2021-22 budget also earmarks $372 million to expedite the distribution of COVID-19 vaccines, and includes $4.5 billion for programs to drive economic growth and job creation once restrictions on normal activities have been lifted. These programs include $575 million in grants to small businesses and nonprofits, in addition to the $500 million for such grants implemented in late 2020 amid forced business closures. The proposal also allocates up to an additional $50 million for the California Rebuilding Fund, a public-private partnership, to support up to an additional $125 million of low-interest loans to underserved small businesses throughout the state.

California’s distinctive approach to market capitalism also emphasizes climate sustainability, using both carbon pricing and efficiency standards to achieve ambitious decarbonization targets. Under a 2018 state law, 60% of electricity must come from renewable resources by 2030, and 100% by 2045. California runs the world’s fourth-largest cap-and-trade system and will be setting even lower caps (and thus a higher carbon price) next month. In September 2020, Newsom announced an executive order requiring that zero-emission vehicles account for 100% of new car sales by 2035. His proposed budget seeks $1.5 billion to accelerate the infrastructure investment needed to achieve this goal.

President-elect Joe Biden has just announced a $1.9 trillion emergency rescue plan to counter the pandemic’s surge and provide substantial relief to workers, families, small businesses, and state and local governments. Prompt congressional passage of this plan is a critical first step in the renovation of America’s outdated neoliberal version of capitalism. As the economy recovers from the deep and uneven COVID-19 recession, the US must “build back better” by strengthening its social safety net, increasing public investment in education, health care, and other public goods, and rejoining the global charge against climate change. Lessons from the more successful variants of market capitalism in Europe and California point the way forward.

Four Ways Biden Can Boost the Global Economy

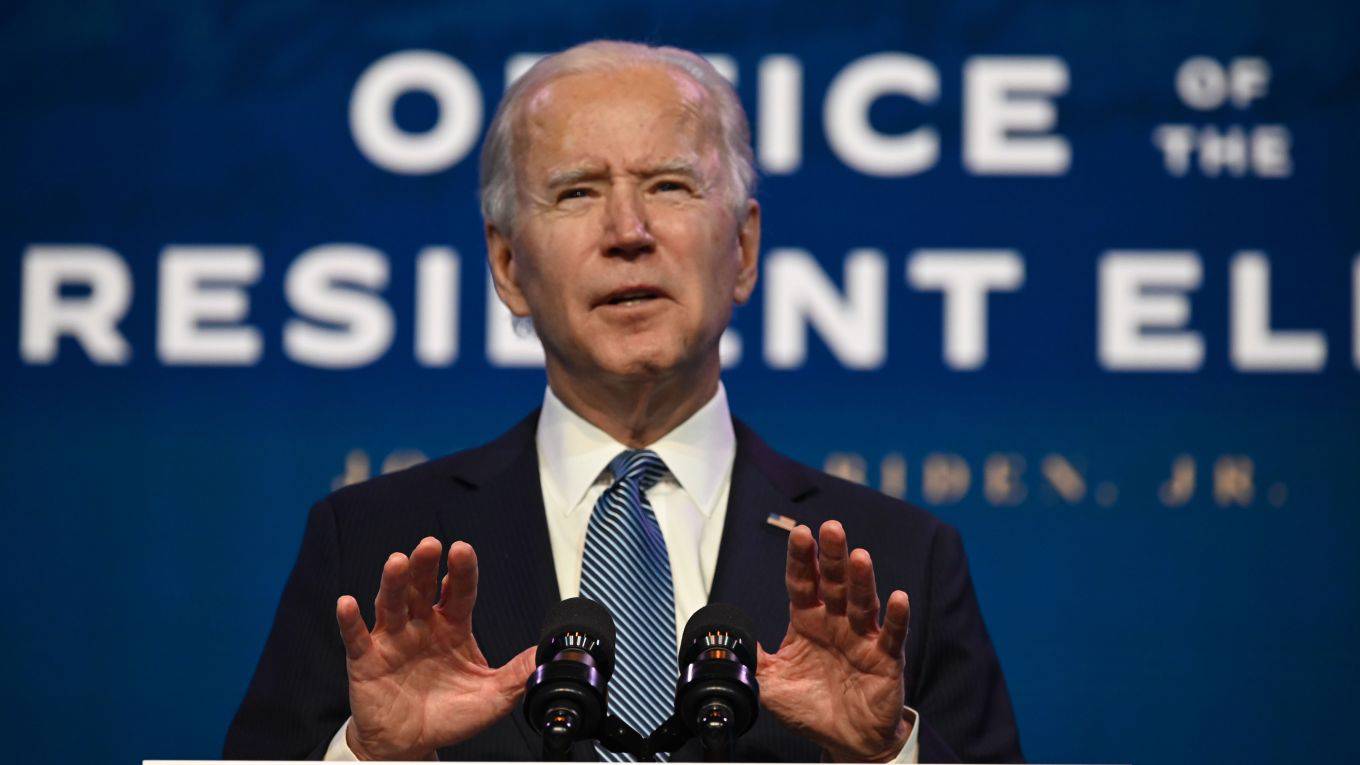

The US is nowhere near as economically dominant as it was even a decade ago. Yet President-elect Joe Biden can take several relatively simple steps that would have far-reaching benefits for the US economy, the American people, and the rest of the world.

NEW DELHI – On January 6, when a mob of US President Donald Trump’s supporters breached the Capitol with shocking ease, the world’s already-low expectations of the United States plummeted. And yet, when it comes to the global economy, there are immediate steps President-elect Joe Biden can take to boost the world’s – and especially developing economies’ – prospects.

To be sure, the limits of US global leadership are significant. After Trump’s presidency, even America’s closest allies harbor serious doubts about its reliability and values, and about the effectiveness of its government. The Trump administration’s botched COVID-19 response, including an inept vaccine rollout, reinforced the perception of national derangement. The Capitol insurrection – which Trump incited, with the goal of disrupting Congress’s certification of Biden’s electoral victory – drove it home.

Even on the economic front, the US is nowhere near as dominant as it was a decade ago, let alone a generation ago. Add to that a razor-thin Democratic majority in the US Senate, and the Biden administration’s ability to implement economic policies that reverberate positively worldwide would seem to be limited.

It is not. Biden does not need congressional approval to implement measures that would have far-reaching benefits for Americans and the rest of the world.

The first is to drop all objections to a World Trade Organization proposal to waive temporarily certain intellectual-property obligations in response to COVID-19. The proposal – introduced by India and South Africa, and cosponsored by other developing countries – aims to remove barriers to timely access to affordable medical products related to the “prevention, containment, or treatment” of COVID-19.

This is in line with WTO rules: the Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual-Property Rights (TRIPS) agreement allows for compulsory licensing. Moreover, the WTO specifies public-health emergencies as adequate cause under TRIPS to issue compulsory licenses that would allow more companies to produce essential drugs. It is difficult to imagine a more appropriate situation in which to apply this provision.

A lower price for COVID-19 vaccines and drugs would benefit everyone, including the advanced economies, whose public budgets are under significant strain. And yet the US has led the advanced economies in blocking the proposal. This benefits only one group: multinational pharmaceutical companies.

This isn’t a matter of ensuring that these companies recoup their costs. The COVID-19 vaccines have been developed on the back of public research and were funded almost completely by public budgets. Even with the temporary suspension of intellectual-property rights, the companies that developed them will profit handsomely.

Allowing these companies to retain patent monopolies on COVID-19 vaccines would prolong the pandemic for everyone – adversely affecting public health and the economy – for the sake of letting a few huge companies line their pockets. If, however, the Biden administration leads the advanced economies in supporting the temporary suspension, countless lives would be saved, and the global economic recovery would accelerate.

Likewise, the Biden administration does not need congressional approval to allow the International Monetary Fund to provide a new allocation of Special Drawing Rights to all its member countries. The US blocked the IMF’s request for such an allocation – worth $500 billion – last April. (India also blocked the request, but if the US withdraws its objection, India is unlikely to resist. In any case, India has little voting power.)

At this point, however, a $500 billion allocation is nowhere near enough; a $2 trillion allocation would be far more effective in bolstering the ailing global economy. Nonetheless, even an initial $500 billion worth of SDRs would provide short-term relief to a wide range of developing economies, especially those with heavy debt burdens.

A third priority for the Biden administration should be to cooperate with other countries to create an effective global system for taxing multinationals’ profits. As the Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation has shown, this would not be difficult to do. The first step would be to set a minimum effective corporate tax rate of 25% worldwide.

The share of a company’s profits taxed in a particular country would be determined according to a formula that included sales, employment, users (for digital companies), and capital. That way, multinationals could no longer avoid taxes by artificially shifting reported profits to lower-tax jurisdictions.

The Trump administration vehemently opposed action to tax multinationals fairly. For example, when France decided to tax the revenue of US digital giants like Facebook, Apple, and Google, it imposed retaliatory tariffs, claiming that the tax discriminated against US companies. The Biden administration should take the opposite approach, working with other countries to ensure a victory for governments and people worldwide.

Biden has already vowed that, on his first day in office, his administration will take the final step that can immediately boost the global economy: rejoining the Paris climate agreement. By doing so, the US will commit not only to meet specific targets for reducing greenhouse-gas emissions, but also to provide financial assistance to vulnerable developing countries.

While the Paris agreement has its limitations, it is currently our best hope for decarbonizing the world economy. And America’s influence is essential to make it work. In fact, after Trump announced in 2017 that he was withdrawing the US from the accord – claiming that it placed an “unfair economic burden” on American workers, businesses, and taxpayers – some other countries reduced their commitments.

More recently, however, major economies, from China to the European Union, have made ambitious new pledges. Even US businesses have begun to recognize that investing in a green transition is in their own interest.

By recommitting to the Paris agreement, Biden will accelerate global progress on climate change and provide additional support to post-pandemic economic recovery. We can hope that his administration will quickly pluck the other low-hanging fruit as well.

The Post-Trump Reconstruction of America and the World

For decades, the United States has lacked a fully credible and feasible overall strategy for backing liberal democracy. To restore the right kind of US global leadership, President-elect Joe Biden's administration should develop one.

WASHINGTON, DC – The inauguration of US President-elect Joe Biden on January 20 will usher in momentous change for the better for the United States. It may also signal a unique opportunity to bolster liberal democracy around the world.

Such optimism about liberal democracy’s global prospects is not widely shared, given the recent rise of illiberal populist governments around the world. Such governments have sought to dismantle the separation of powers, judicial independence, press freedom, and political opponents’ ability to function freely. Many argue that, for reasons transcending Donald Trump, liberal democracy will remain in retreat.

Moreover, the recent storming of the US Capitol by an armed mob incited by Trump has arguably undermined America’s capacity to lead by example. After all, almost the entire Republican Party had continued to support Trump despite his increasingly unstable and anti-democratic behavior.

But the situation has changed rapidly following the insurrection at the Capitol. A large majority of US voters have condemned the violence, and support the peaceful transfer of power. Although 73% of Republican voters still think that Trump is protecting democracy, the president’s approval ratings fell to all-time lows after the pro-Trump riot.

Trump is also losing some GOP congressional support. On January 13, ten Republicans in the House of Representatives joined with Democrats in voting to impeach Trump for a second time, for “incitement of insurrection.” And Trump will face his Senate trial with current Majority Leader Mitch McConnell reportedly keen to rid the GOP of him.

Much will depend on whether and how those responsible for the coup attempt on January 6 are held to account. But Trump’s violent last spasm may eventually lead to a decrease in polarization and a strengthening of America’s democratic institutions, especially if a large part of the electorate were to support swift measures to fight racial injustice, including by strengthening voting rights.

But the legacy of Trump is not the only obstacle Biden must overcome to present the US as a strong global leader of liberal democracy. While many argue that America supported democracy for decades before Trump was elected in 2016, the US frequently backed authoritarian governments and overthrew elected ones, partly to counter the Soviet Union, but also out of economic self-interest.

For example, the US deposed Iran’s democratic government in the 1950s, facilitated the 1973 military coup against Chilean President Salvador Allende and similar actions in Central America and the Caribbean, and continues to support totalitarian regimes in some oil-producing countries. Despite America’s claims, there was little sustained sincerity in its post-war support of liberal democracy.

The incoming administration led by Biden and Vice President-elect Kamala Harris has a unique opportunity to conduct a much more consistent and credible policy in the coming years. Effectively championing liberal democracy need not and should not entail interfering in other countries’ affairs. Some genuine national-security threats – involving weapons of mass destruction or foreign-backed terrorism, for example – may require intervention abroad. But intervention to achieve regime change, even if to help install democracy, should never be an objective in itself, because a foreign-installed regime will almost always have great trouble gaining legitimacy.

As Harvard University’s Joseph Nye recently pointed out, Biden’s policy choices will not be so clear-cut. US broadcasts that support democracy should not be labeled as foreign intervention, and the rise of social media has no doubt created new gray areas. The line between amplifying anti-authoritarian views and inciting regime change may not always be easy to draw. Moreover, the world will need new types of “arms-control” understandings as new technologies are weaponized and security and economic objectives become harder to separate.

Nonetheless, the Biden-Harris administration should set its sights high. For starters, it should have a comprehensive domestic agenda that prioritizes justice and democracy, and finally eradicates America’s “original sin” of white supremacy, which would enable the US truly to lead by example.

To that end, the US should vocally advocate liberal democracy as the governance system that can best fulfill universal human aspirations. And it should gradually move to a system of alliances in which the allies that America commits to protect militarily (including in cyberspace) are all democracies.

Biden should pursue a basic strategy of respecting all countries’ national sovereignty, except in cases where the responsibility to protect a group from mass atrocities requires the international community to act. When the United Nations Security Council is unable to reach a decision, owing to a veto by one of its permanent members, a case-by-case approach to the use of armed intervention is inevitable.

The US needs to work with all willing countries, regardless of their political regimes, in pursuing common goals such as limiting the danger of climate change and providing global public goods, including pandemic prevention. Another high priority is to develop standards and norms to govern cyberspace, artificial intelligence, and biotechnology. Arms control treaties in the Cold War probably spared the world nuclear war – and they are still required.

For decades, the US has lacked a fully credible and feasible overall strategy for backing liberal democracy. The Biden administration should now try to develop one. In general, it should recognize that addressing many old and new challenges requires a revived multilateralism – and thus effective international institutions supported by the US.

There will of course be gray areas, but the perception that America’s intentions are sincere would take the Biden administration far. The US still has a lot of soft power – despite Trump’s best efforts to destroy it – and Biden and Harris have the right fundamental mindset to provide global liberal-democratic leadership. They should not let the opportunity pass.

How Will Biden Intervene?

Broadly defined, intervention refers to actions that influence the domestic affairs of another sovereign state, and they can range from broadcasts, economic aid, and support for opposition parties to blockades, cyber attacks, drone strikes, and military invasion. Which ones will the US president-elect favor?

CAMBRIDGE – American foreign policy tends to oscillate between inward and outward orientations. President George W. Bush was an interventionist; his successor, Barack Obama, less so. And Donald Trump was mostly non-interventionist. What should we expect from Joe Biden?

In 1821, John Quincy Adams famously stated that the United States “does not go abroad in search of monsters to destroy. She is the well-wisher to the freedom and independence of all. She is the champion and vindicator only of her own.” But America also has a long interventionist tradition. Even a self-proclaimed realist like Teddy Roosevelt argued that in extreme cases of abuse of human rights, intervention “may be justifiable and proper.” John F. Kennedy called for Americans to ask not only what they could do for their country, but for the world.

Since the Cold War’s end, the US has been involved in seven wars and military interventions, none directly related to great power competition. George W. Bush’s 2006 National Security Strategy proclaimed a goal of freedom embodied in a global community of democracies.

Moreover, liberal and humanitarian intervention is not a new or uniquely American temptation. Victorian Britain had debates about using force to end slavery, Belgium’s atrocities in the Congo, and Ottoman repression of Balkan minorities long before Woodrow Wilson entered World War I with his aim to make the world safe for democracy. So, Biden’s problem is not unprecedented.

What actions should the US take that cross borders? Since 1945, the United Nations Charter has limited the legitimate use of force to self-defense or actions authorized by the Security Council (where the US and four other permanent members have a veto). Realists argue that intervention can be justified if it prevents disruption of the balance of power upon which order depends. Liberals and cosmopolitans argue that intervention can be justified to counter a prior intervention, prevent genocide, and for humanitarian reasons.

In practice, these principles are often combined in odd ways. In Vietnam, Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson argued that the US military was countering North Vietnamese intervention in South Vietnam. But the Vietnamese saw themselves as one nation that had been artificially divided on the basis of realist Cold War balance-of-power considerations. Today, the US has good relations with Vietnam.

In the first Gulf War, President George H.W. Bush used force to expel Iraq’s forces from Kuwait to preserve the regional balance of power, but he did so using the liberal mechanism of a UN collective security resolution. He considered himself a realist and refused to intervene to stop the shelling of civilians in Sarajevo, but after devastating images of starving Somalis on US television in December 1992, he deployed troops for a humanitarian intervention in Mogadishu. The policy failed spectacularly, with the death of 18 US soldiers under Bush’s successor, Bill Clinton, in October 1993 – an experience that inhibited US efforts to stop the Rwandan genocide six months later.

Because foreign policy is usually a lower priority than domestic issues, the American public tends toward a basic realism. Elite opinion is often more interventionist than that of the mass public, leading some critics to argue that the elite is more liberal than the public.

Nonetheless, polls also show public support for international organizations, multilateral action, human rights, and for humanitarian assistance. As I show in Do Morals Matter? Presidents and Foreign Policy from FDR to Trump, no one mental map fits all circumstances. There is little reason to expect the public to have a single consistent view.

For example, in the second Gulf War, American motives for intervention were mixed. International relations specialists have debated whether the 2003 invasion of Iraq was a realist or a liberal intervention. Some key figures in George W. Bush’s administration such as Richard Cheney and Donald Rumsfeld were realists concerned about Saddam Hussein’s possession of weapons of mass destruction and the local balance of power; but “neo-conservatives” in the administration (who were often ex-liberals) stressed the promotion of democracy and the need to maintain American hegemony.

Outside the administration, some liberals supported the war because of Saddam’s abominable human rights record, but opposed Bush for failing to obtain the institutional support of the UN, as his father had in the first Gulf War.

Broadly defined, intervention refers to actions that influence the domestic affairs of another sovereign state, and they can range from broadcasts, economic aid, and support for opposition parties to blockades, cyber attacks, drone strikes, and military invasion. From a moral point of view, the degree of coercion involved is important in terms of restricting local choice and rights.

Moreover, from a practical point of view, military intervention is a risky instrument. It looks simple to use, but it rarely is. Unintended consequences abound, implying the need for prudent leadership.

Obama used force in Libya, but not in Syria. Both Trump and Hillary Clinton said in 2016 that the US had a responsibility to prevent mass casualties in Syria, but neither advocated military intervention. And there was remarkably little discussion of foreign policy in the 2020 election.

Some liberals argued that the promotion of democracy is America’s duty, but there is an enormous difference between democracy promotion by coercive and non-coercive means. Voice of America broadcasts and the National Endowment for Democracy cross international borders in a very different manner than the 82nd Airborne Division does.

In terms of consequences, the means are often as important as the ends. Where will Biden land on the spectrum of interventions intended to promote security, democracy, and human rights? We may find an encouraging clue in his history of good judgment and contextual intelligence. But we must also bear in mind that sometimes surprises occur, and events take control.

No comments:

Post a Comment