Love the world anyway

Talking to Hannah Arendt's new biographer about propaganda, evil, forgiveness, hope, and loving the world enough to believe that it can change

Welcome to The.Ink, my newsletter about money and power, politics and culture. If you’re joining us for the first time, hello! Click the orange button below to get this in your inbox, free. Please consider becoming a paid subscriber to support this work.

For me, this strange, unsettling moment in American life is defined by the feeling that nothing is possible and everything may be.

Last week was the insurrection. Next week, with luck and without a working Parler app, is the inauguration. In between there is dread and hope.

There is a philosopher for every moment, and it’s hard to think of one better suited to the mixed bag of this one than Hannah Arendt — the German-born, Jewish, American political philosopher and author of such enduring works as “The Origins of Totalitarianism” and “Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil.”

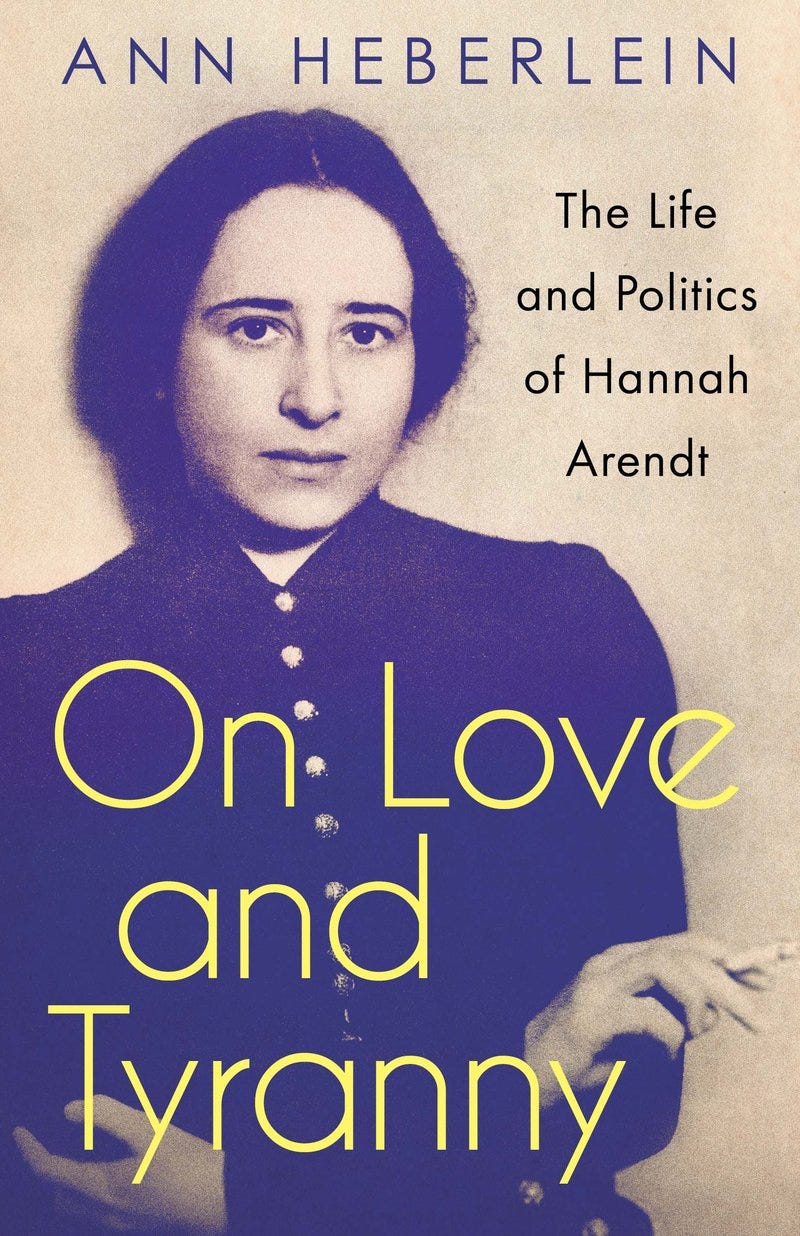

Today I’m bringing you my interview with the author of a new biography, “On Love and Tyranny: The Life and Politics of Hannah Arendt.” Ann Heberlein is a Swedish scholar and author, and I knew I wanted to talk to her when I read these words about what she believes we today can learn from Arendt: “to love the world so much that we think change is possible.”

But first: a programming note: I will be doing my regular live chat/webinar/Zoom-where-it-happens thing today at 1 p.m. New York, 10 a.m. Pacific time, and 6 p.m. London time. They’re really fun and engaging, and people have started to organize sidebars with each other to collaborate on their civic projects. It’s great. If you haven’t yet, subscribe today to join us. Subscribers will get login details beforehand.

Subscribing to The Ink is the best way to keep it free and open to all, and to support independent media that hopefully makes you think and enlivens your conversations. I appreciate your support for this undertaking.

“To love the world as it is, in all its brokenness”: a conversation with Ann Heberlein

ANAND: You’ve written a new biography of Hannah Arendt, a thinker with profound relevance to this moment. For people who’ve never heard of her before, or merely pretend to know her work on Zoom cocktail hours, who was she, and why did you want to write about her?

ANN: Hannah Arendt’s life is like a novel, a story full of obstacles and victories, love and hate, happiness and suffering, setbacks and successes.

She was born in Hanover, Germany, in 1906, eight years before the outbreak of World War I, grew up during World War II, was persecuted and expelled by the Nazis, was interned in the French concentration camp of Camp Gurs, and, in 1941, escaped to the United States, where she built a life with her husband, Heinrich Blücher.

Hannah is known as a philosopher, a title she only reluctantly accepted. She devoted herself primarily to the realm of political philosophy, and, using her own experiences as a driving force, explored topics such as evil, responsibility, anti-Semitism, communism and totalitarianism, rights and obligations.

I personally became acquainted with Hannah Arendt’s thinking during my own dissertation. My doctoral dissertation was an analysis of the concept of forgiveness, and Arendt’s reasoning about the concept of forgiveness struck me as very original, and it appealed to me.

Arendt writes about forgiveness in relation to the Holocaust, and believes that there are things that are in their very essence unforgivable — actions that are so horrific that it is not possible to impose a reasonable and fair punishment — and if the punishment is impossible, then forgiveness is also impossible. While arguing for that patent “unforgivability,” under certain conditions, she nevertheless displayed a very unusual ability to “forgive her neighbor” on a personal level.

Sometime during my doctoral studies, I stumbled upon Elzbieta Ettinger’s book, Hannah Arendt/Martin Heidegger, which describes the love affair between the young Hannah, then a student at the University of Marburg, and the much older Martin Heidegger, a professor at the same university. Their love affair was complicated by the fact that he was married and that she was Jewish. Heidegger, of course, was to become a member of the German National Socialist Party.

Many years later, when Arendt had established herself in the United States and the war was over, she returned to Europe to search for and collect Jewish books, manuscripts, and other cultural artifacts, on behalf of the Jewish Cultural Reconstruction organization. She decides to take up contact with Heidegger again. Exactly what happened between them on February 7, 1950, when they meet in Freiburg, we do not know — but we may understand from their correspondence that they reconciled. They remained close friends, perhaps lovers, until up until Heidegger’s death.

This inconsistency, for lack of a better word, fascinated me. Hannah Arendt is not just a brilliant thinker whose work has greatly influenced our view of humanity, evil and goodness. She is also a complex and contradictory person who transgressed geographical borders, as well as our social conventions. I wanted to try to describe that.

ANAND: Your book first caught my eye with these words: “What can we learn from the iconic political thinker Hannah Arendt? Well, the short answer may be: to love the world so much that we think change is possible.” This is a moment when so many people rightly feel the opposite. Tell us how Arendt came to that place, and what her idea might mean for us?

ANN: “It would be wonderful to live, if only world history were not so awful,” Arendt once wrote in a letter to her friend Kurt Blumenfeld in 1952. It is easy to sympathize with her feelings. The world and humanity often disappoint us.

In 1962, Arendt had an accident on her way home to her flat, close to Central Park in New York. The taxi she was traveling in was hit by a lorry and she was promptly taken to Roosevelt Hospital. She described the incident in a letter to her friend Mary McCarthy shortly afterwards: “During a floating moment, I had the feeling that it was up to me to decide whether I wanted to live or die. Even though I did not think that death was terrible, I thought that life actually is quite beautiful and that I like to live a lot.”

Arendt had been reconciled with the incompleteness of life, with the fragility of the world. She believes that it is a duty to love the world. Amor mundi, “love of the world,” means caring for life so that it can continue to exist. We must be able to love the world as it is, in all its brokenness and imperfection. To achieve that requires hope, hope that change is possible, hope for the future.

Hope is necessary. Without hope, without the ability to imagine a life beyond its present circumstances, a person may be prone to give up. But someone who has the ability to embrace that hope may have a capacity to survive atrocities and inhumanity. Despite the resignation Hannah expresses in the letter to Kurt Blumenfeld, she was a woman who had that ability to hope. The hope that there was a life beyond the horrors of the concentration camps helped her to endure the internment of Camp Gurs, the life of the being a refugee, her escape from Europe, the exile in the United States, and coping with a new and unfamiliar language on a professional level.

ANAND: Arendt famously coined the phrase “the banality of evil.” It’s a much-used, much-abused, much-misunderstood phrase. What did she mean by it?

ANN: This concept is certainly one of the most misunderstood in the history of political philosophy. It is not the evil act that is to be considered as “banal,” nor should the consequences of any evil deed be regarded as banal. It is the motive behind these evil acts that may be seen as banal. Arendt thus questions whether evil intentions and evil motives are always a prerequisite for evil. According to her, there is not always a relationship between these.

Arendt coined the term in connection with her presence at the trial of one of the highest-echelon SS officers, Adolf Eichmann, who was accused by an Israeli court of crimes against humanity. She observed the trial as a reporter for The New Yorker in Jerusalem in April 1961 and was struck by how ordinary and mundane Eichmann appeared. He did not look at all like the monster you may have imagined. He appeared, as she writes, as “a sad and unimaginative bureaucrat who has just done his job,” neither demonic, nor fanatical.

Hannah believed that evil deeds often are performed or caused by people who have no evil intent. The sad truth is that evil deeds are often performed by people who have not reflected on the moral dimension of their acts, people who have not taken sides, people who choose “to obey their orders,” as Eichmann stated in his defense.

ANAND: What does the Arendt lens tell us about the presidency of Donald J. Trump? What was this? Tyranny? Authoritarianism? Autocracy? How do you situate these last four years in American life in the history that she wrote about?

ANN: It would be very presumptuous of me to speculate on how Hannah Arendt would have interpreted Donald Trump’s four years in power — but I would nevertheless like to highlight some aspects of a more general nature, namely lies and propaganda.

Propaganda is an indispensable part of the creation of a totalitarian state. “The masses must be won through propaganda,” she writes in “The Origins of Totalitarianism.” The political lie is just as indispensable to motivate the masses.

President Trump has given ample examples of both. He has been exceptionally good at speaking to what Nietszche called “ressentiment,” that is, a feeling of inferiority and powerlessness, of being forgotten, despised, and invisible.

The ressentiment creates hatred. Hatred towards those who are considered to be part of some kind of establishment and hatred because of perceived or real historical wrongdoing. All totalitarian movements in history, such as fascism or communism, have addressed that kind of ressentiment, and every kind of totalitarian movement in the future will do the same, regardless of political color. Despite the fact that Trump belongs in every sense of the word to the establishment — he owns economic assets; he enjoys political power and has the capacity to shape the image of our common reality — he has allied himself with the ressentiment-driven fractions of society.

A dictatorship is not created overnight. A genocide or a civil war does not arise out of thin air. It requires preparation in the form of lies, propaganda, and a conscious division into “us and them,” belonging and non-belonging.

ANAND: In her analysis of Eichmann and the notion of following orders and the result, I wonder how you would analyze the legions of disinformation-addled followers who stormed the Capitol last week.

ANN: To a certain extent, their actions are logical from within the framework of their worldview. Their leaders (who by some are worshiped in an almost grotesque way) have convinced them that they have been betrayed, that they have been robbed of their choice and of their victory. A dependent flock is easy to manipulate for a charismatic leader who spares no means.

The ironic thing is that their self-image is that they are the ones who have seen through the lie and seen the truth: The rest of the world is deceived.

Eichmann claimed for his defense, when he was accused of having initiated and participated in genocide, that he “only followed orders” and “did his duty.” It is an interesting thought that President Trump’s most fervent adherents — Proud Boys, QAnon — perceive that they have a mission, and a duty to act. The tragedy is that they seem convinced that they are doing the right thing.

There is, however, a difference between a bureaucrat like Eichmann and the activists storming the Capitol Hill. Eichmann thought he was maintaining law and order, while the activists sees themselves as front-line revolutionaries who want to challenge it all.

ANAND: What was Arendt’s understanding of what evil was, ultimately? Is it lurking in everybody, waiting for expression, or concentrated in some? Is given by nature or nurtured by societies?

ANN: The potential to perform evil acts or to accept evil acts by others is present in us all. The antidote is not, as one might think, goodness, but rather reflection. Another concept that is central to Arendt’s thinking is responsibility. Since every individual is free and has the power to influence the world and other people’s lives through their attitudes and actions, they also have a responsibility.

We are responsible for what we do and for what we do not do. People have a tendency to obey, a penchant to seek refuge in authority. This worried Arendt, who never ceased to emphasize the responsibility of each individual to find out for themselves how things are going rather than blindly following a leader.

Arendt's thinking around these matters has been followed up by moral philosophers such as Jonathan Glover and Philip Zimbardo. Both of them emphasize the importance of the environment, the group, for the actions of an individual and obedience to participate in evil actions. “It is not the apple that is rotten, but the basket,” as Zimbardo puts it in “The Lucifer Effect.”

ANAND: We all need a cigarette right now, even though nobody should smoke. What was up with Arendt and the cigarettes? Was she ever photographed without one?

ANN: Well, she just liked to smoke. There is actually a rather sweet anecdote about Arendt and her relationship to tobacco. In 1933, she attends a lecture at the Zionist Federation of Germany. There she gets to know the previously mentioned Kurt Blumenfeld, who is the organization’s chairman. The two immediately come to like each other, and Kurt, who appreciated Arendt’s intellect and independent nature, greets her a few weeks later with a box of deliciously scented Cuban cigars. She loved cigars, and to the dismay of her husband at the time, Günther Stern, she even smoked them demonstratively in public (something that normally was associated with street prostitutes at the time).

According to Hannah, she could not write without having a cigarette hanging in the corner of her mouth. When in her later age, a doctor tried to convince her to stop smoking due to a heart condition, she just whisked that recommendation away. She wrote to her friend Mary McCarthy: “Of course this man held his usual sermon — ‘take it easy,’ ‘quit smoking,’ and so on. But the thing is that I absolutely refuse to adapt my life to what is considered as healthy; I will go on to live as I want.” Of course, that meant that she continued to smoke until she passed away.

ANAND: One of the things that’s been hard for me in the Trump years, despite being a very early person to call out his autocratic and white supremacist ways, is that a certain part of me always struggled to imagine it actually happening here, even as I knew that it was. Can you talk about Arendt’s analysis of how, in democracies, as with objects in side-view mirrors, tyranny can be closer than it appears?

ANN: One thing we can learn from Arendt is the importance of being on one’s guard and not to indulge in conspiracy theories or wishful thinking. We should all exercise a healthy skepticism, a certain amount of suspicion. Arendt was suspicious of Hitler and his National Socialism very early, but her worries and fears were often waved away by many of her friends.

In the autumn of 1936, a few years after she was forced to flee Germany, she was in Geneva to attend the founding of the World Jewish Congress. Her concerns about the situation in Europe is clear in the letters she sends to her husband, Heinrich Blücher, who is in Paris. She is clearly frustrated that no one, not even the Jews themselves, seems to take the escalating persecution of Jews seriously: “Who will raise their voice about this if we do not?” she wrote helplessly to Heinrich.

Undoubtedly, the catastrophe — the Holocaust — was much closer at hand than most people could have imagined. Hannah was desperate that people around her did not seem to understand what was going on and the rising threats. Why did they not understand? Perhaps because of a lack of imagination, perhaps because of intellectual lethargy and convenience. One lesson to learn is to hope for the best, but always keep a keen eye out for the worst.

ANAND: You are especially interested in an aspect of Arendt that is less well known — her ideas on love. Why do you think this aspect of her work is less famous, and what does she have to tell us about love?

ANN: Arendt’s doctoral dissertation dealt with the concept of love in Saint Augustine — a rather odd choice for a Jewish philosopher, one may think. She identifies three types of love in “Love and Saint Augustine,” the lustful, erotic love; the altruistic and self-sacrificing love; and the reciprocal, friendly love.

Above all, I find her reflections on the latter type of love, the reciprocal affection that concerns friendship, interesting. Friendship can be described as “love without pain,” a deep, warm relationship that is characterized by care and reciprocity and lacks the destructive elements of jealousy, desire, and possessiveness.

Arendt herself was a very friendly person. Since she and Heinrich Blücher had no children, their friends became their family. One of her lifelong friends, Hans Jonas, said Hannah had “a rare gift for friendship.”

Arendt also had interesting thoughts about relationships and monogamy, something she wrote extensively about in her Denktagebuch (intellectual diary) and in letters to her friends. After World War I, everything that had previously been considered a basic social institution was challenged: the flag, the throne, the altar. When these previously “eternal” points of reference were challenged, other institutions, values, and ideals became relativized as well — such as marriage. Already in the interwar period, Arendt and her husband lived in what we would today call “an open relationship.”

Why is Arendt’s reasoning about love not better known? I do not know, since she addresses the issue quite thoroughly in her book “The Human Condition.” Perhaps it has to do with some sort of hierarchy among our sentiments, as they have been interpreted within political philosophy. We are attracted by what we experience as breaking away from the ordinary, such as evil or cruelty. Perhaps that is somewhat encouraging in a sense, that we perceive love as so obvious that we do not have to reflect so much about it. But for Arendt it definitely was important.

ANAND: What does Arendt’s work have to tell us about how a country like America could be put back together, not only from the Trump years but from all the unresolved hatreds and traumas that have intersected with new channels of disinformation, new economic dislocations, and the like?

ANN: Let me return to some of the concepts I have already mentioned: responsibility, reflection, and truth. Let me also throw in another one, namely reason. Arendt was not much for overheated activism. She believed in the sensible, reasoned conversation, in appealing to people’s responsibility, and in encouraging people to reflect.

Hannah Arendt loved America. In letters to friends who lived in Europe, she described the ease of dealing with Americans, the ability to discuss even serious and difficult things without starting a war. She appreciated the American mood, which she found less gloomy and more lighthearted than is common in the Old World: “Their conversations are conducted without fanaticism and their argumentation is available to a large number of people,” she wrote of her American friends in a letter to Karl Jaspers in 1946.

I believe that Hannah would have experienced disappointment and dismay over the American condition that we experience today, marked as it is by polarization and distrust, enmity and contempt, between different groups.

Perhaps the beginning of the solution, of reconciliation and healing, can be to strive to recapture the open and inclusive conversation and move away from fanaticism and exclusion.

Ann Heberlein is a Swedish academic and author. You can order her new book, “On Love and Tyranny: The Life and Politics of Hannah Arendt” now. This interview was edited and condensed for clarity.

No comments:

Post a Comment